THE TIDE GOES OUT: ASSESSING PRIVATE MARKET MANAGER STABILITY

For more than a decade, both the number of funds and amount of capital raised by private market General Partners (GPs) had been on an upward trajectory. For GPs, attracting and retaining talent was relatively easy over this period, with industry tailwinds attracting high-caliber professionals who could be incentivized with rising compensation packages and the promise of expanding opportunities. These trends accelerated during the post-pandemic boom, which saw unprecedented levels of fundraising and deal activity. As in many other industries, some firms altered their trajectory for a new world in which those levels of activity and growth would be the norm going forward, ramping up hiring, capital deployment, and fundraising ambitions. Just a few quarters removed from those halcyon times, private market activity has slowed significantly, and structurally higher rates and macroeconomic uncertainty are expected to create a more challenging operating environment in the years ahead.

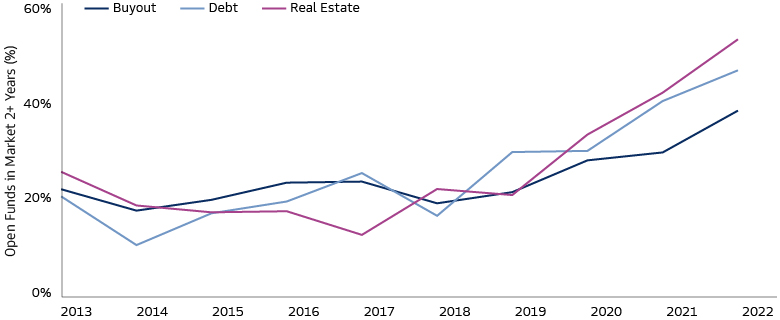

With Limited Partners (LPs) facing the combined impact of the numerator and denominator effects, fundraising timelines have been extended and the challenges are expected to persist in the coming quarters. Many funds are struggling to meet their goals and are facing the prospect of a fund size that is smaller or unchanged from the prior vintage. Smaller fund sizes could translate to less potential carry to distribute amongst the investment teams, as well as present structural issues for GPs who have grown accustomed to a certain level of management fees and/or require higher levels of management fees to support organizations that were expanded in the anticipation of growth. The need for GPs to dedicate more time and effort to raising new funds could potentially become a distraction for investment team members. This not only introduces risk for strategy execution, but also could lead to morale and motivation issues for team members who may be asked to spend a disproportionate amount of time raising capital rather than deploying it.

Source: PitchBook. As of December 31, 2022.

In addition to the broad fundraising slowdown, following a rapid proliferation of sub-strategies by some GPs, many appear to have changed tack and are redoubling efforts on existing strategies rather than branching into new areas. As there are potentially fewer opportunities for talent to rise through the ranks and assume new responsibilities, the risk of organizational instability and team turnover at GPs may also rise—particularly amongst mid-career professionals who may no longer anticipate the same trajectory with their current firm. Headlines suggest that some GPs have started reducing head count, and there are also expectations for consolidation within the industry as even well-performing firms may find it difficult to find a viable path forward (see sidebar). We believe these challenges for GPs are important considerations for LPs in both assessing current fund positions and evaluating new opportunities.

Maturation Leads to Consolidation

The private equity industry has seen relatively steady growth for several decades, across both the number of firms and total assets under management. A handful of GPs have achieved scale and more direct access to capital markets via public listings. With this access to financing, some have turned to acquisitions to expand both their fund offerings and talent pools. The 50 largest GPs completed 116 strategic deals in the decade through 2022, but the pace is accelerating with nearly 40% of those transactions coming in the last two years. Many of these merger and acquisition deals between GPs involve established firms, where the track record and longevity of the strategy being acquired are major assets; other deals for less-established GPs can be more akin to so-called acqui-hires of startup engineering teams, where the main asset being acquired is the people. As a result, the largest GPs now tend to have diversified strategy offerings that allow them to lean into and capture different opportunities as the market and environment evolves. Other GPs looking to follow suit and build multi-strategy platforms will likely need to raise capital, either from a public listing or GP stake sale.

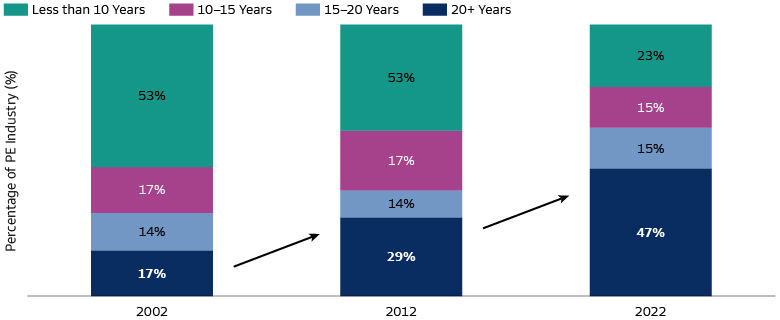

At the same time that large GPs are becoming more acquisitive, the proliferation of GPs and funds in recent years also means that the number of potential targets has never been higher. In addition to cyclical factors that may lead to organizational instability, many established GPs are at a critical juncture; nearly half of GP firms that are 20-35 years old have yet to initiate a succession plan. At the other end of the spectrum, the proliferation of new firms over the last 15 years means that many of the firms operating today have yet to experience a full market cycle. Many of these firms aggressively expanded amidst the broad tailwinds of the last decade, and now that the market has turned and fundraising has grown more difficult, the need to recalibrate could lead some to pursue strategic alternatives.

Source: Preqin. As of December 2022. Includes all private equity buyout firms with AUM greater than $1 billion.

Assessing Organizational Stability

Asset Base and Strategy Mix

Capital is the lifeblood of business, and this is particularly true for investment management firms. A strong, stable capital base is essential for private market managers not only to deploy capital effectively and efficiently through market cycles, but also to properly compensate talent and provide a compelling trajectory for upward mobility. As with many businesses, an investment firm tends to be best positioned when the client base (i.e., LPs) is diverse and unconcentrated. Some simple ways to quantify a GP’s LP base include assessing the total number of LPs at both the firm and fund level, as well as the relative commitments of the largest LPs and the percentage of re-ups. The type of LP is pertinent too; similar types of LPs may behave similarly in terms of their commitment decisions.

We believe strategy diversification should also be considered, with pros and cons for different models. Large, diversified asset managers with multiple fund strategies may be able to allocate resources, especially non-investment resources, across a platform depending on where they are most needed, which would be expected to change over the course of a cycle. In addition, manager-level revenue streams for diversified GPs are often more consistent, as the lumpiness of performance and fundraising associated with a particular strategy is reduced when aggregating multiple strategies. As a result, the firm can provide a smoother and more predictable compensation experience for many investment professionals. At the other end of the spectrum, single-strategy GPs should theoretically be able to run leaner teams and tie compensation more directly to performance, with the tradeoff being less opportunity to mitigate strategy-specific headwinds. Additionally, single-strategy firms inherently have fewer avenues for junior talent to be promoted or assume more responsibility.

In today’s environment, the most challenged GPs may be those that are in the midst of an expansionary phase, potentially with fund strategies in their first few vintages; these GPs may have to contemplate whether certain strategies are viable going forward, and how their recent growth plans may need to be recalibrated for new realities. To understand the GP’s priorities and the potential for distraction caused by ancillary strategies, investors can analyze the number of strategies that the firm has managed over time, including the average age and asset under management (AUM) change across strategies, as well as develop an understanding of which investment team members are dedicated to a particular strategy or will be required to work across multiple strategies. This analysis should be supplemented with conversations with senior leadership and considerations for how economics are shared between the flagship team and those running other strategies.

Team Structure

Team turnover is a straightforward and common way to address stability, but some research has shown a positive correlation between turnover and performance. This potentially counterintuitive finding can be attributed to a combination of short-term performance improvements when “bad performers” are asked to leave along with long-term performance benefits from turnover that enables a firm to “adapt and replenish skills.”1 Indeed, the strategies and skillsets required to succeed are likely to differ based on the prevailing macro environment and particular segment of the business cycle. To that end, rather than simply equating a lack of turnover with stability, we believe investors should be looking to assess how a GP is adapting—whether through team structuring, upskilling, additions, or (in some cases) reductions—to maintain an edge and deliver alpha in an ever-evolving market. Furthermore, LPs should consider if there is enough accountability and whether everyone is being held to a high enough standard, including more tenured professionals who over time may play a less active role in the organization.

Investment firms necessarily increase in complexity as they grow, but organizations need to strive to maintain clear lines of communication and simplicity in their structure. Stability starts at the top with strong leadership. Investment acumen is essential, and while leaders need to have confidence and trust their skills and process, they also run the risk of hubris and consolidating decision-making. Successful GPs tend to limit the number of direct reports for both senior leaders and mid-level managers; these flatter hierarchies may lead to enhanced collaboration and facilitate opportunities for professional development and upward mobility by increasing exposure for junior team members. The career progression for specific roles should be clear, and a firm-level succession plan should be in place to ensure continuity (see sidebar).

With turnover alone proving insufficient to evaluate the team and structure, due diligence should include an evaluation of the investment committee composition and process. Incorporating diverse viewpoints can create a more resilient organization and lead to greater buy-in from team members. The ownership structure of the firm is important in assessing not only how current economics are shared, but also to understand how the structure may impact collaboration and long-term planning.

Motivation

The view that “people are our greatest asset” has become cliché in many fields, but in private equity, we believe people truly are the foundation. Retaining and hiring talent are cited as primary objectives for GPs of all sizes.2 As private markets become a more integral part of capital markets and investment portfolios, the competition for experienced talent is intensifying. The ability to properly motivate talent may become more challenging in the current environment, as a decrease in exits is likely to impact carry payouts in the near term while the potential for weaker fund-level performance could reduce compensation pools over the long term.

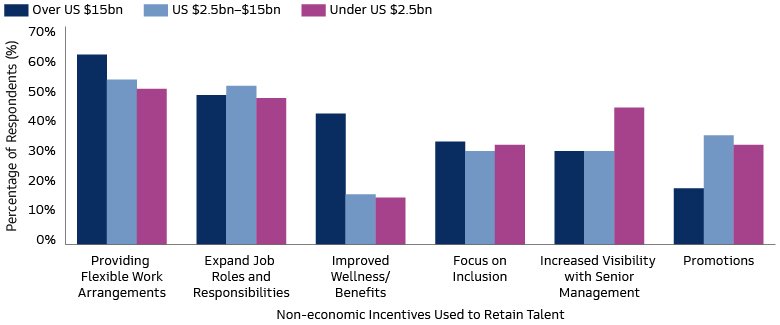

Compensation is unquestionably a primary motivator for many workers across a broad range of fields—and private equity is no exception. Investors can assess the overall GP commitment to the fund, including how it is financed and contributed to, as well as the allocation of carry, to understand the complex economic incentives. But employees are increasingly valuing other factors in the workplace. Research has shown that the level of talent at an investment firm is best explained when evaluating both economic incentives and non-economic incentives,3 including opportunity to operate autonomously, achieve mastery, and work towards a purpose. Increasingly, flexible working arrangements (i.e., remote work) are a factor too. In addition to assessing formal policies, diligence should include time with professionals from all levels of the GP to get a qualitative view of morale.

Source: EY. The 2023 EY Global Private Equity Survey. As of January 18, 2023.

Talented professionals will seek out challenging, rewarding opportunities—as such, GPs need to have a plan in place to ensure they have ways of motivating and rewarding top talent. In addition to the risk of losing talent to competitors, GPs must also consider the potential for employees to launch their own fund if not presented with opportunities. While raising a first-time fund is notoriously difficult, especially in today’s more challenging fundraising environment, those with the most success often come from established GPs where they have been able to demonstrate an initial track record of success.4

Searching for Solid Ground

As the market environment has turned, many GPs are grappling with new realities in fundraising and managing their own firm. These challenges also represent an important variable for LPs to consider in both evaluating current holdings and considering new fund commitments. Organizational stability is always an important factor for private market investing—where a single fund commitment typically lasts for more than a decade—but it is perhaps even more paramount today as market tremors create the potential for cracks in firms’ foundations.

1Cornelli, Simintzi, and Vig, “Team Stability and Performance: Evidence from Private Equity,” May 2019.

2EY, “Three ways CFOs are adapting to emerging private equity trends,” Jan 18, 2023

3Goldman Sachs Asset Management as of 2015 and Ouimet, Paige and Tate, Geoffrey A., Firms with Benefits? Nonwage Compensation and Implications for Firms and Labor Markets (July 5, 2023). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4112463 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4112463

4Private Equity International. “LPs pull back from first-time funds” As of December 1, 2022.