Trade Routes Realigned: From Integration to Fragmentation

Global Fragmentation

It’s the end of globalization as we know it

The free movement of goods, capital, people, and ideas across borders was one of the most powerful forces to have shaped the post-war world. But after driving economic expansion for decades and peaking around the time of the global financial crisis, the old era of globalization looks to be over. A new phase of international trade is underway shaped by a global pandemic, Russia’s war on Ukraine, Middle East tensions and preeminent geopolitical powers—notably the US and China—competing with each other.

A reversal of broad global economic integration toward more fragmentated pockets of trade between like-minded partners has given rise to terms like “reshoring”, “nearshoring”, or “friend-shoring”—phrases that featured in more than 20,000 announcements by US businesses in 2023 alone.1 With geopolitical conflicts and tensions rising, governments and corporations look set to continue prioritizing supply chain security, resource security, and national security in the years ahead.

Reality not rhetoric

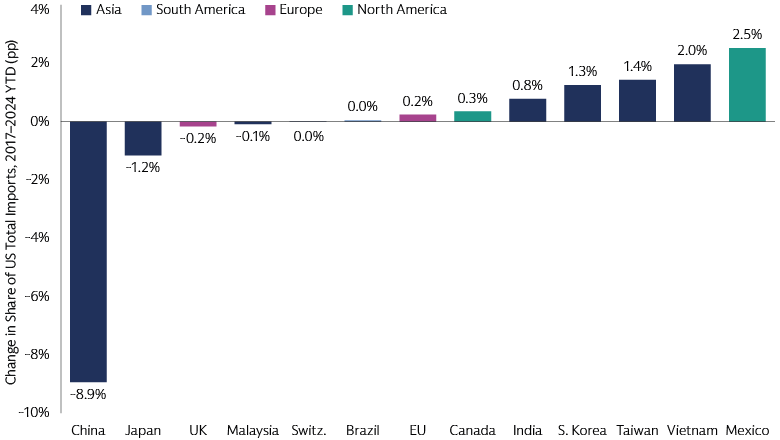

The question of where companies should build factories and reconfigure production and sourcing sites requires new answers; evidence suggests answers are being found. As trade restrictions on goods, services and investment have more than tripled since the onset of the US-China trade war in 2018, rhetoric around locational choices is turning into reality.2 This new dynamic is resulting in US manufacturing market share shifting from China to other partners, including Latin America, especially Mexico given its geographical proximity (nearshoring), and reliable trade partners in Asia (friend-shoring), such as India. We believe the nearshoring and friend-shoring of production lines remains in its early stages and will continue to ramp up as economies expand new industrial capacity and manufacturing networks over time.

Source: US Census Bureau, and Goldman Sachs Asset Management. As of August 2024. Latest is June 2024. Figures are seasonally-adjusted. Past performance does not predict future returns and does not guarantee future results, which may vary.

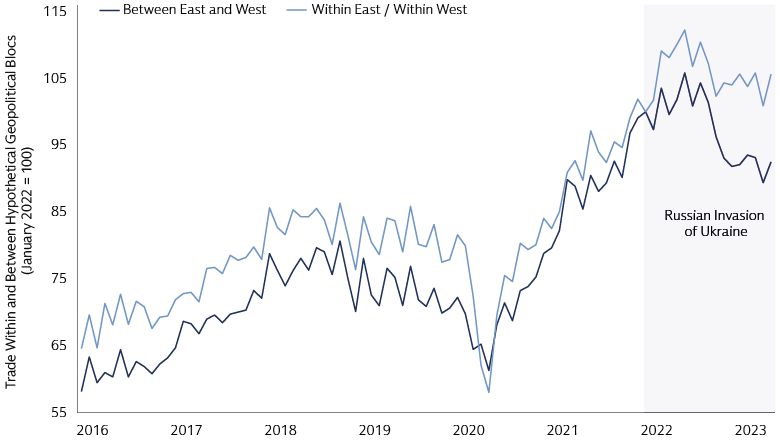

China is reconfiguring its own supply chains in response to increasing cost pressures and trade frictions. Mainland companies are increasingly nearshoring production to countries more aligned along on both economic and geopolitical dimensions, such as Cambodia and Vietnam. To the extent that trade tensions are here to stay, this trend should continue. Beyond the US and China, there has been a broader shift of global trade flows progressively fragmenting along geopolitical lines since the Russia-Ukraine conflict began.

Source: World Trade Organisation (WTO), Trade Data Monitor, and Goldman Sachs Asset Management. As of May 2023. Figures are seasonally adjusted. The full breakdown of the classification of economies in the hypothetical East and West blocs can be found under this link: (ersd202310_e.pdf (wto.org), on pages 17 and 18. Ukraine has been excluded due to the war.) Past performance does not predict future returns and does not guarantee future results, which may vary.

Government policies aimed at ensuring supply chain, resource and national security are reinforcing the trend of global fragmentation. In the US, legislation is providing funding and financial incentives to build onshore semiconductor chip manufacturing facilities (CHIPS and Science Act). Other bills are intended to accelerate the deployment of clean energy as well as clean vehicles, buildings and manufacturing (Inflation Reduction Act). Elsewhere, in Europe, the REPowerEU policy added new measures to the Green Deal to reduce dependency on Russian gas and promote investment in renewables through the Green Industrial Action Plan. A key element is the regulation establishing a framework for ensuring a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials, widely known as the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA). These examples of government-led actions in Europe and the US present opportunities for companies to fill the gaps created by a more fragmented geo-economic backdrop.

Counting the Economic Costs and Consequences

Barriers and disconnects

Globalization acted as a multi-decade catalyst for a catch-up in incomes across countries. It also led to a reduction in poverty and lower prices (and greater variety) of goods, especially for low-income consumers. The delinking of international trade puts these gains at risk. For instance, fragmented economic policies make it more challenging for countries to deliver on the climate transition. Reduced co-ordination around global health threats, including large-scale pandemics, may increase costs at a human and financial level, adding to challenges posed by aging demographics. More digital barriers and disconnects are likely to create different technology and talent ecosystems, uneven development and adoption of artificial intelligence, and new and complex cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

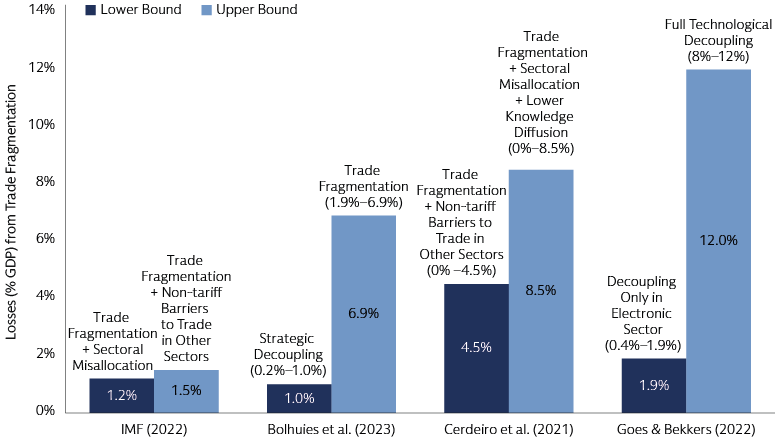

Estimates of the cost of fragmentation vary depending on the nature and composition of geopolitical and/or trade blocs, the types of barriers imposed, and the ability of suppliers to replace one factor of production with another. That said, most studies conclude that, on balance, global fragmentation will lead to higher inflation, tighter monetary policy—in the absence of changes to inflation targets—and lower, more uneven, economic growth across countries.

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Trade Organization, Vox EU CEPR, and Goldman Sachs Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only. Estimates of long-term losses (% of GDP) from Global Trade Fragmentation come from various studies. Numbers refer to GDP losses that are not directly comparable across papers as some refer to global GDP while other refer to specific regions or countries. “Strategic decoupling” refers to a scenario in which trade fragmentation is limited to the elimination of all trade between Russia on one hand and the US and the EU on the other, as well as the elimination of trade in high-tech sectors between China and the US and EU. The economic and market forecasts presented herein are for informational purposes as of the date of this presentation. There can be no assurance that the forecasts will be achieved.

The impact on economic growth appears to rise alongside the degree of fragmentation. In other words, more trade barriers result in less growth. Technological decoupling seems to amplify losses from trade restrictions significantly as productivity is largely determined by access to technologies, knowledge, and processes. While the world will adjust, technological decoupling may lead to less efficient outcomes over the long term, even as structural growth drivers of semiconductor demand and digitization remain intact. Moving production from lower-cost countries to closer—whether physically or geopolitically—but higher-cost countries is not cheap. There are other less-obvious costs to consider. Some emerging market and low-income countries are potentially at risk due to loss of knowledge spillovers. A broader trend of de-globalization could pose headwinds to select economies over a longer time horizon. Not every economy will be impacted to the same extent. By contrast, several countries are already emerging as beneficiaries of supply chain reconfiguration, with the US experiencing the most prominent changes.

Investing in a Fractured World

Industrial renaissance

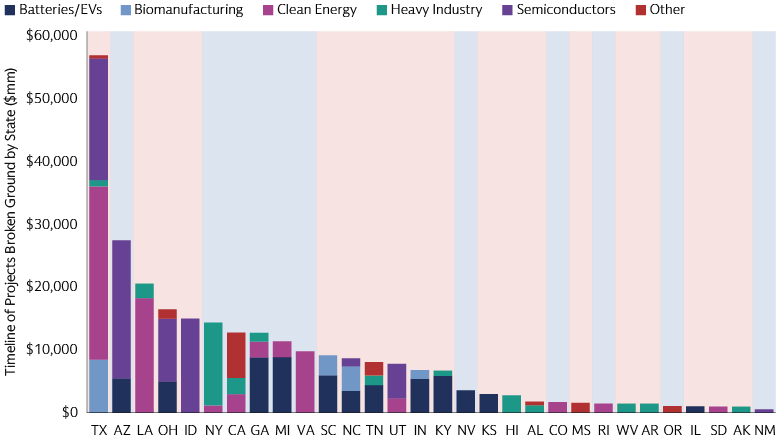

While fragmentation represents a downside risk to the global economy, reshoring is sparking an industrial renaissance in select developed markets, notably the US. The rebuilding of US production and economic independence is creating unique long-term investment opportunities, including among companies capitalizing on policy measures aimed at achieving supply chain, resource and national security. Private companies have pledged $910 billion of investments into leading 21st century technologies, including over $395 billion (40%) committed to semiconductors and electronics, the single largest category, followed by $177 billion into electric vehicles and batteries, and $167 billion into clean power.3 Simultaneously, $480 billion in Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to date across the Biden-Harris Administration spans 60,000 projects—from road to rail—across states and territories, mobilizing private sector manufacturing and making it easier for businesses to transport and ship their goods.

Source: Dodge Data and Analytics, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. As of September 13, 2024. Value of mega projects breaking ground across US states and by sector ($mn). The background signifies Republican (red) and Democrat (blue) states during the 2020 Presidential election. Mega project refers to $1 billion-plus projects spread across semiconductors, battery/EV plants, heavy industry, clean energy manufacturing, and a variety of mostly public projects. Clean energy covers projects that include manufacturing and export of products such as hydrogen, LNG and Ammonia. Clean Power projects include power gen via wind, water and solar energy.

Production of advanced semiconductor chips is the most prominent example of an area profoundly affected by the reshaping of global supply chains. Semiconductors are a backbone of the connected world and key to the modern digital economy, powering cutting-edge technologies from EVs to the next generation handsets to the Internet of Things. Over 90% of these vital components are currently manufactured in just one country: Taiwan.4 At the start of 2024, the Biden administration set a new target for the US to produce 20% of the world’s most advanced semiconductor chips by 2030; the US currently makes 0% of the so-called leading-edge chips crucial for everything from mobile phones to AI to quantum computing.5

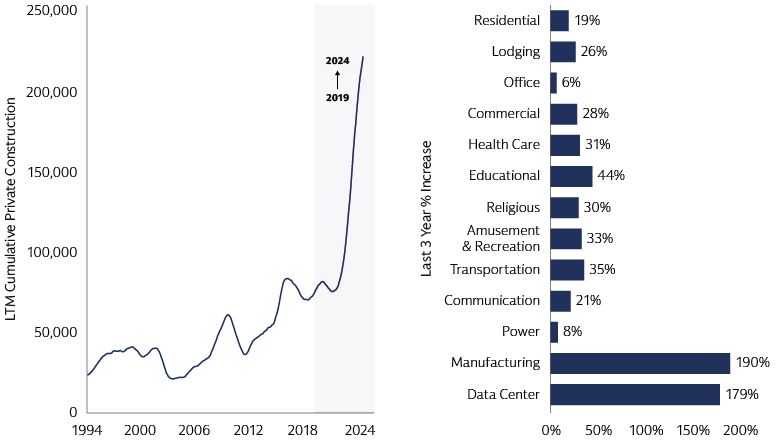

Due to offshoring trends over the last two-and-a-half decades, most developed countries’ industrial manufacturing segment has stagnated. In the US, the semiconductor industry is a microcosm of that trend. Between 1995 and 2020, the US’s share of global GDP high-tech industries—semiconductors, but also precision tools and communication equipment—declined by 11 percentage points.6 Companies that survived have developed strong barriers to entry over time and could experience accelerated growth in the next decade and beyond as manufacturing returns home. The need to rebuild physical manufacturing hubs and warehouses in developed nations is also critical. Prior to 2021, construction spending had been steady with no growth until the CHIPS and Science Act and IRA legislation. Since 2022, the segment has experienced exponential growth with most of it driven by manufacturing facilities and data centers, which in the last three years have increased by 190% and 179% respectively.7

Source: US Census Bureau, Bloomberg, Goldman Sachs Asset Management. Left hand side: Data from January 31, 1994, to July 31, 2024. Right hand side: Data from July 31, 2021, to July 31, 2024.

New production facilities need to be highly cost efficient, sustainable and flexible, leveraging automation and connectivity. The “picks and shovels” of reindustrialization—companies designing, building and outfitting the "factories of the future”—represent a large universe of investment opportunities, spanning several economic sectors. They include companies that supply construction aggregates and heavy building machinery, producers of cement and other materials used for building production facilities, data centers and infrastructure. Key gases such nitrogen, xenon, neon and helium are critical elements needed to drive manufacturing; leaders in this space are well positioned to gain, too. We also expect companies that provide automation solutions to optimize industrial processes, make them safe, secure and reliable to experience growing demand.

Data centers’ power systems require highly sophisticated management solutions, to be supplied by reliable and innovative producers of electronic equipment and software to enable effective manufacturing and ensure environmental controls. Energy distribution requirements are also getting more complex; producers of electrical equipment that can not only manage power onsite but also connect these facilities to the electrical grid to power them will become critical players in the game. Data centers that continually run powerful AI models require 4x more electricity and generate extraordinary amounts of heat. Manufacturers specializing in cutting-edge cooling technologies, in air ventilation and refrigeration systems, stand to benefit from the trend. As the world moves from trade integration to fragmentation, we expect governments to be laser focused on ensuring economic security. From an economic standpoint, there will be winners and losers, but for investors we think the ongoing reconfiguration of supply chains offers investment opportunities across equity markets and sectors.

The Upshot

The US is emerging as a key beneficiary of global fragmentation as favorable legislation is quickly mobilizing vast amounts of capital in strategic sectors like semiconductor manufacturing, electric vehicles, and energy. We also see opportunities in countries with a competitive advantage in a critical aspect of global supply chains, like India whose large labor and consumer markets, edge in pharmaceuticals, digital connectivity, and production-linked incentives position it to be the next global manufacturing hub. Countries with a unique ability to make themselves attractive for nearshoring, offshoring, or friend-shoring, like Mexico or Vietnam, also stand to benefit.

Not every company will gain to the same extent or will be able to reconfigure its business model with the same efficiency to meet new demands. Active management based on solid fundamental research adds value in finding winning companies in developed and emerging countries that are best positioned to take advantage of this powerful, multi-year reshoring trend; those that have strong competitive moats are innovative and flexible. We believe any attractive stocks and sectors are currently underrepresented in market-cap weighted indices, making active management ever more important to provide the right exposure.

1 Bloomberg. As of April 23, 2024. Data includes "all" mentions of "onshoring", "reshoring", and "nearshoring", across Bloomberg, social media platforms, and newspaper articles.

2 International Monetary Fund (IMF), Global Trade Alert Data. As of August 25, 2023.

3 WhiteHouse.gov. As of September 20, 2024.

4 McKinsey & Company. As of April 2021.

5 US Department of Commerce. As of February 2024.

6 McKinsey. As of April 12, 2021.

7 US Census Bureau, Bloomberg, Goldman Sachs Asset Management. As of July 31, 2024.