Green Bonds: Connecting Fixed Income Capital to The Global Climate Transition

The transition to a sustainable economy is no longer an abstract goal. To build the vital infrastructure needed to reduce the impact of climate change, companies, governments and supranational institutions are developing breakthrough technologies and policies that will accelerate the shift to clean energy.

Financing this economic transformation will require vast amounts of capital. One recent estimate puts the average annual investment needed to achieve a net zero global economy by 2050 at $9.4 trillion.1 In response, public and private investors are mobilizing capital to support innovative solutions in areas such as renewable energy, green infrastructure, energy efficiency and carbon capture.

The global bond market will be an important source of investment to drive the climate transition. Yet until recently, investors who aimed to reduce the carbon footprint of their fixed income portfolios without sacrificing liquidity and returns had few compelling options.

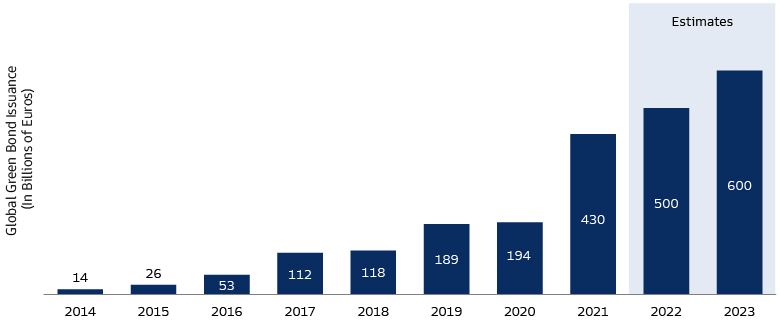

The rise of green bonds is changing that. Once a niche product, these bonds that finance environmentally beneficial projects have entered the investing mainstream. The market is expanding, with average growth of about 90% per year from 2016 to 2021.2 Thanks to this rapid growth and the widening range of mutual funds offering exposure to green bonds, investors can use them to replace a portion of the conventional bonds in their fixed income allocation.

What Are Green Bonds?

Green bonds are standard fixed income securities with a green element. Their financial characteristics such as structure, risk and return are similar to those of traditional bonds. The main difference is that the goal for green bonds is to exclusively finance projects or activities with a specific environmental purpose.

This commitment to advancing the climate transition goes back to the first green bond, issued in 2007 by the European Investment Bank (EIB), the lending arm of the European Union (EU). The funds raised by that five-year bond were earmarked for projects in renewable energy and energy efficiency, contributing to the EU’s climate change strategy.3

Since then, green bonds have become an approximately €1.5 trillion market.4 Dominated in the early years by multilateral development banks such as the EIB and the World Bank, which issued its first green bond in 2008, the market has seen the range of issuers expand to include companies and governments across the globe seeking investment to drive their plans to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and guard against physical climate risks. The investor base has also expanded to include a growing number of traditional fixed income investors, not just those focused primarily on impact and environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria.

Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management and Bloomberg. Estimates are for full year 2022 and 2023. For illustrative purposes only.

Driving Market Momentum

We believe the momentum in the green bond market reflects a growing commitment to building a sustainable economy, driven by a combination of issuers’ increasingly determined climate-change responses and investors seeking to support the transition to a low-carbon economy while generating financial returns. The EU’s first green bond, issued in 2021, is a good example of issuers’ ambition and investors’ appetite coming together. Not only did the bond raise a record €12 billion for green and sustainable investments across the bloc, but it was also more than 11 times oversubscribed, with orders from a wide range of investors topping €135 billion.5

Policymakers are also playing a key role in the expansion of the green bond market by creating the right incentives for sustainable investment. They also set standards for measuring the environmental impact of projects that can help support green bond issuance and investment. A government that encourages the production of electric vehicles, for example, provides car companies with an opportunity – and an incentive – to finance research and development with green bonds, while motivating investors to own those bonds to align their financial and environmental investment goals.

Expansion Fuelled by the Global Climate Push

From the start, the global response to climate change has helped drive the growth of the green bond market. These efforts reached a watershed in 2015, when the United Nations adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a 15-year action plan for protecting the environment, ending poverty and reducing inequality.6 Later that year, world leaders at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) signed the Paris Agreement, an international treaty that aims to cut GHG emissions and limit global warming this century to well below 2°C compared with pre-industrial levels.7

These two global agreements sparked further expansion of sustainable investing, including green bonds, by driving home the urgent need for investment and setting critical targets. They provided issuers and investors in the green bond market with a common purpose and a framework for identifying investment priorities and assessing progress towards global climate goals. Increasingly, issuers are aligning their securities with these global initiatives, and asset managers offering exposure to the green bond market are using the goals spelled out in the SDGs and the Paris Agreement to screen bonds for potential investment and to demonstrate the impact of their portfolios.

Key Milestones in the Global Climate Push and Green Bond Market

Green Climate Initiatives

2015: Global – At the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21), countries signed the Paris Agreement.

2019: EU – The European Commission (EC) presented the EU Green Deal, an ambitious decarbonization plan to reach net zero by 2050.8

2020: EU – The EU Taxonomy Regulation defined what economic activities are considered “green” by contributing to one of the six environmental objectives9: 1) climate change mitigation, 2) climate change adaptation, 3) protection of water, 4) transition to a circular economy, 5) pollution prevention, and 6) biodiversity & ecosystems.

2021: Global – At COP26, over 190 countries adopted the Glasgow Climate Pact,10 which requires countries to revisit and strengthen their 2030 emission reduction targets, and update their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in 2022 to better align with the Paris Agreement.

2022: EU – The EC unveiled its REPowerEU plan11 aimed at improving energy security and fast forwarding the energy transition.

2022: China’s latest 5-year plan (its 14th) encouraged more optimized renewables development.12

2022: US – The Biden Administration designated $2.8 billion to strengthen domestic battery supply chains, supporting the development of EVs.13

2022: US – The Inflation Reduction Act – signed into law by President Biden on August 16 – provides about $386 billion in energy and climate spending over 10 years, with related tax incentives up about $265 billion from the prior run rate.14

Green Bond Market

2007: European Investment Bank issued the first Climate Awareness Bond.15

2008: World Bank issued its first green bond.

2010: The Climate Bonds Initiative launched the Climate Bond Standard.

2013: Vasakronan, Sweden’s largest real estate company, issued the first corporate green bond.16

2013: The state of Massachusetts issued the first US municipal green bond.17

2014: ICMA published the Green Bond Principles.18

2015: The People’s Bank of China issued its own green bond guidelines.19

2015: The United Nations adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a 15-year action plan for protecting the environment, ending poverty, and reducing inequality.20

2016: Poland issued the world’s first sovereign green bond.21

2016: Apple issued a $1.5 billion green bond, which was the largest green bond to be issued by a US company at the time.22

2017: France issued a €7 billion debut green bond.23

2017: Fiji became the first emerging market country to issue a sovereign green bond.24

2017: The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Capital Markets Forum developed green bond standards tailored to meet the needs and commitments of their own market.25

2021: The UK and Colombia issued inaugural green sovereign bonds.26

2021: The European Union raised €12 billion through green bonds as part of its NextGenerationEU program.27

2021: Walmart issued a $2 billion green bond in the US dollar market, the largest corporate green bond at the time.28

2022: Canada entered the market with its inaugural C$5 billion green bond.29

2022: Singapore made its market debut with a S$2.4 billion green bond with a 50-year maturity, making it the longest-dated green bond issued by a sovereign.30

Setting Green Bond Standards

Another key factor supporting expansion of the green bond market has been the development of guidelines such as the Green Bond Principles and the Climate Bonds Standard. These have promoted transparency and credibility in the green bond market by encouraging issuers to provide information that investors need to make informed decisions about a bond’s environmental credentials. While this has helped increase investors’ confidence in these products, regulators around the world are considering further rule changes to address the challenge of “greenwashing,” the practice of making overstated or misleading claims about the environmental ambition of a project, asset, or activity.

The Green Bond Principles, published by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) in 2014, contain project categories that are broad in scope, but they all contribute to environmental objectives such as climate change mitigation and adaptation, natural resource conservation, biodiversity conservation and pollution prevention and control. By setting out best-practice guidelines for issuers to promote greater transparency and accurate disclosure of key information, they have helped the market become more standardized, facilitating tradability and supporting the development of green bonds into a full-fledged segment of the fixed income market.

The Climate Bonds Initiative developed its own set of guidelines, the Climate Bond Standard, in 2010 with the goal of promoting market growth by building confidence in the environmental credentials of green bonds. To facilitate this, the Standard has sector-specific eligibility criteria including performance metrics for each green bond category.

Importantly, the Green Bond Principles and Climate Bonds Standard are both voluntary, like most of the market standards that have been developed over the years. This means that issuers themselves label their bonds as green based on guidance from regulators, stock exchanges and market associations.

In addition to global efforts, regional and national guidelines have also been developed. Among these is the EU’s influential taxonomy, which established a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities. The taxonomy, based on a regulation that entered into force in 2020, was designed to provide a clear definition of sustainability and common terms to increase transparency in the market.31 In 2015, Chinese regulators issued their own green bond standards, which helped stimulate rapid expansion of the country’s green bond market. China amended its standards in 2022 to bring them into closer alignment with global standards.32

How Do Green Bonds Fit in a Fixed Income Portfolio?

Green bonds’ transparent use-of-proceeds structure and their focus on delivering measurable environmental benefits make them an effective tool for issuers to finance the climate transition. For investors, green bonds typically carry no significant additional costs compared with conventional bonds, but they do help improve a portfolio’s alignment with the SDGs and the Paris Agreement.

In some aspects, green bonds are similar to conventional bonds. They come in investment and non-investment grade, though most corporate green bonds are investment grade. The credit profile of a green bond is the same as that of a traditional bond from the same issuer, and green bond holders have the same recourse to the issuer. In terms of yield, there is no significant difference between a green and a non-green bond.

Replacing a portion of a conventional fixed income portfolio with green bonds can potentially bring benefits beyond helping investors achieve their climate ambitions. Green bonds can finance environmentally beneficial assets such as green buildings that could bear a lower credit risk over time. They can help reduce climate change-related risks in portfolios resulting from policy changes such as carbon taxation that could lead to stranded assets. Green bonds may also come with tax incentives that can improve investors’ real returns.33

There are differences between green and conventional bonds, of course, and they go beyond the green label. For example, agencies and supranational issuers occupy a larger share of the green bond market than they do in the broader fixed income market, while sovereign debt accounts for a smaller share. The green bond market is dominated by euro-denominated bonds, whereas in the overall market the US dollar occupies the top spot. The aggregate green bond benchmark has a longer duration than the non-green equivalent, increasing sensitivity to rising interest rates. These and other differences could affect investors’ decisions about how much they want to allocate to green bonds and which conventional bonds they can replace in their portfolios.

Managing Greenwashing Risks

Greenwashing can take many forms. For example, if an issuer has no strategy for adopting a more sustainable business model, the credibility of a green bond issuance could be diminished. Companies with long-term sustainability strategies could be considered more forward-looking, innovative, and resilient to the negative spill-over effects of climate change.

Stringent selection criteria can help in mitigating some of these risks. Investors should pay particular attention to bond documentation, the green impact of a bond – including alignment with accepted green bond standards – and the sustainability strategy of a bond issuer. Engagement with green bond issuers can also protect investors from reputational greenwashing risks as well as supporting the assessment of creditworthiness. Engagement is particularly important when it comes to high-yield and emerging market issuers, as these companies or governments often have fewer resources to devote to thorough sustainability reports.

Ultimately, the goal of any fixed income investment is to maximize risk-adjusted returns, and green bonds are no different. Selecting an asset manager with a strong fundamental research process, detailed reporting, and robust risk management is crucial, and can help investors avoid controversies, limit downside risk and uncover the opportunities with the most attractive potential returns.

Does Green Impact Come at a Cost?

Another much-debated topic among investors is the “greenium,” or green premium, which implies that supporting environmental concerns by investing in green bonds comes at the cost of financial performance. The idea is that a green bond with the same terms as a conventional bond such as rating and maturity can trade below conventional peers in terms of spread levels. As a result, holding such bonds to maturity could yield a lower return.

In theory, there is no reason why the fact that a bond is green should affect its price. Green bonds rank on an equal footing with other bonds with the same financial characteristics from the same issuer. Although green bond issuance does involve some additional costs relating to third-party review and certification, these have been declining over time.

One aspect of the market that has supported the greenium has been the combination of high investor demand for green bonds and relatively short supply. As issuance increases, the willingness of investors to pay more for green bonds may wane. For example, a report published in 2021 by the Association for Financial Markets in Europe estimated that green premia for corporate green instruments had “significantly tightened” to virtually zero basis points.34 While there is some evidence that indicates the existence of a greenium in some less-developed sectors of the green bond market, across the market as a whole, the greenium has narrowed considerably in recent years.

Engines of Growth

Europe has long been the main driving force in the green bond market, fueled by a diverse mix of issuers across the region’s major national markets. In the first half of 2022, five of the top six green issuers globally were European: the EU itself, Germany, France, the EIB and the Netherlands. The only issuer from outside Europe was the Bank of China, ranking second, according to a Climate Bonds Initiative report.35

Europe’s leading role in the market is reflected in the dominance of euro-denominated green bonds, which accounted for 63% of the market at the end of the third quarter of 2022. Dollar-denominated bonds issued by corporates and local authorities in the US as well as other issuers around the world were a distant second at 22% of the market, though this share is increasing. The remaining 15% of the market was spread across currencies led by the sterling and the Canadian dollar.36

We expect the European market to continue to expand in the years ahead, led by the ambitious issuance plans announced at the EU level. The EU plans green bond issuance of as much as €250 billion by the end of 2026 to finance its NextGenerationEU program, which supports the bloc’s economic recovery from the pandemic and green development.37 Issuance on that scale would make the EU the world’s largest green bond issuer.38

We also expect to see growth pick up as green bonds continue to become a mainstream market segment in the US, the world’s largest fixed income market. One limit on expansion of the US green bond market is that issuance continues to be driven by corporates and local authorities, and it remains unclear if the Treasury will start issuing green bonds in the future.

In China, the recent amendment of green bond standards helps align the domestic standards with global principles, increasing transparency and fuel market growth by making Chinese green bonds more attractive to international investors. Elsewhere in emerging markets, where issuance has been slow, green bonds could allow companies and governments to broaden their investor base by appealing to sustainable investors.

Green Bonds Growth in the Years Ahead

We expect continued growth in the green bond market driven by the three main forces behind its rapid expansion in recent years: increasing issuance to finance the energy transition and address physical climate risks; strong demand from investors seeking potentially attractive returns while helping advance the shift to a low-carbon economy; and support from policy makers by creating incentives and setting standards that encourage green investment.

Extraordinary market volatility and rising interest rates slowed the supply of new green bonds in 2022 by hindering some issuers from tapping capital markets, just as we saw in the broader bond market.39 Looking ahead, we estimate there will be about €600 billion of green bond issuance in 2023, potentially taking the market to more than €2 trillion as sovereigns and corporates continue to step up their environmental ambitions.40

Some 140 countries have announced or are considering net zero targets covering nearly 90% of global GHG emissions, according to Climate Action Tracker.41 This increase in commitments will likely continue to prompt more countries and supranationals to issue green bonds as an effective way to channel capital into climate-related projects. India, for example, plans to issue 160 billion rupees of sovereign green bonds in the fiscal year ending in March 2023.42

Companies are also increasingly committing to the net zero agenda. By the end of 2021, more than 2,200 companies representing $38 trillion of market capitalization were pursuing credible, science-based emission-reduction targets to bring them in line with the Paris Agreement.43 We expect emerging market corporates and sovereigns to contribute to growth in the US dollar green bond market. Green bonds accounted for 1% of emerging market corporate bond issuance in 2015, but today that share has increased to 18%.44

Investor demand will also continue to spur green bond issuance. While aggressive monetary tightening has challenged demand for bonds in 2022, one pocket of the fixed income market – ESG funds – has proven relatively resilient. This group, which includes dedicated green bond funds, has seen assets under management increase by 3% since the end of 2021, while non-ESG funds recorded a 3% decline.45 In addition, as companies from more sectors and sovereigns in more regions issue green bonds, investors will have more opportunities, which may further stimulate demand.

Finally, we expect the policy environment, including improvements in guidelines and standards, to continue spurring green bond issuance and investment. In addition to tightening its green bond standards in 2022, China committed to more renewables development as part of its 14th Five-Year Plan. In the US, President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act into law in August, providing about $386 billion in energy and climate spending over 10 years, with related tax incentives of up about $265 billion from the prior trend rate.

The transition to a low-carbon global economy is a complex challenge that will require concerted action from governments, companies, investors, policymakers and individuals. One of our fundamental challenges in the years ahead will be to mobilize the substantial sums needed for investment in everything from green infrastructure to the cutting-edge technologies that we will need to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and slow the course of climate change. We believe the continued focus of bond issuers on climate mitigation and adaptation creates strong growth potential for green bonds, and this growth will expand the potential opportunities for investors committed to advancing environmental progress through their fixed income allocations in the years to come.

1 Source: Swiss Re Institute,"Decarbonisation tracker. Progress to net zero through the lens of investment,” as of October 7, 2022.

2 Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Bloomberg. As of December 31, 2021.

3 Source: European Investment Bank, “EPOS II - The "Climate Awareness Bond" as of May 22, 2007.

4 Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Bloomberg. Based on spot exchange rates as of September 30, 2022.

5 Source: European Commission, “NextGenerationEU: European Commission successfully issues first green bond to finance the sustainable recovery,” as of October 21, 2021.

6 Source: United Nations, “Unanimously Adopting Historic Sustainable Development Goals, General Assembly Shapes Global Outlook for Prosperity, Peace,” as of September 25, 2015.

7 Source: United Nations, “The Paris Agreement,” as of November 11, 2022.

8 Source: European Commission, “A European Green Deal,” as of December 11, 2019.

9 Source: EU Taxonomy, as of March 2020.

10 Source: Glasgow Climate Pact, as of December 13, 2021.

11 Source: REPowerEU, as of July 26, 2022.

12 Source: IHS Markit, “China’s renewables 14th Five-Year Plan: Official targets to be remarkably outpaced?” as of July 20, 2022.

13 Source: Energy.gov, “Biden-Harris Administration Awards $2.8 Billion to Supercharge U.S. Manufacturing of Batteries for Electric Vehicles and Electric Grid, as of October 19, 2022

14 Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. GS SUSTAIN: Green Capex US Inflation Reduction Act -- What's transformational, what's supportive, what's underappreciated, as of August 30, 2022.

15 Source: European Investment Bank, “EPOS II - The "Climate Awareness Bond" as of May 22, 2007.

16 Source: Vasakronan “Green financing,” as of September 30, 2022.

17 Source: Bloomberg News, “Massachusetts Green Bonds Mirror World Bank: Muni Deals,” as of June 3, 2013.

18 Source: ICMA, Harmonized Framework for Impact Reporting, as of June 2019.

19 Source: Climate Bonds Initiative, “Roadmap for China,” as of April 2016.

20 Source: United Nations, “Unanimously Adopting Historic Sustainable Development Goals, General Assembly Shapes Global Outlook for Prosperity, Peace,” as of September 25, 2015.

21 Source: Climate Bonds Initiative, “Poland wins race to issue first green sovereign bond. A new era for Polish climate policy?”, as of December 15, 2016.

22 Source: Reuters, “Apple issues $1.5 billion in green bonds in first sale,” as of February 17, 2016.

23 Source: Agence France Trésor, “GREEN OATs,” as of January 24, 2017.

24 Source: World Bank, “Fiji Issues First Developing Country Green Bond, Raising $50 Million for Climate Resilience,” as of October 17, 2017.

25 Source: ACMF, ASEAN Green Bond Standards, as of November 2017.

26 Source: London School of Economics and Political Science, “Green bonds for people, planet and development,” as of October 13, 2021.

27 Source: European Commission, “NextGenerationEU Green Bonds,” as of October 2021.

28 Source: Axios, “Walmart joins the green bond party with $2 billion deal,” as of September 10, 2021.

29 Source: Department of Finance Canada, Press Release, as of March 23, 2022.

30 Source: Monetary Authority of Singapore, Press Release as of August 4, 2022.

31 Source: EU Taxonomy, as of March 2020. It should be noted that the EU taxonomy is neither mandatory nor aimed to be an investment tool.

32 Reuters, “EXCLUSIVE: China tightens green bond rules to align them with global norms,” as of August 24, 2022.

33 Source: Climate Bonds Initiative, “Policy areas supporting the growth of a green bond market,” as of 2022.

34 Source: Association for Financial Markets in Europe, “Q1 2021 ESG Finance Report,” as of March 31, 2021.

35 Source: Climate Bonds Initiative, “Green bonds up 25% in 2nd quarter after volatile start to 2022,” as of August 4, 2022.

36 Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management and Bloomberg, as of September 30, 2022.

37 Source: European Commission, “Questions and Answers: NextGenerationEU first green bond issuance,” as of October 12, 2021.

38 Source: European Commission “NextGenerationEU Green Bonds,” as of January 2022.

39 Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management and Bloomberg. Forecast for annual issuance in 2022 is a range of €450 billion-€500 billion.

40 Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management and Bloomberg. This forecast assumes lower market volatility in 2023 and incorporates our estimate of postponed issuance from 2022.

41 Source: Climate Action Tracker, “CAT net zero target evaluations,” as of November 2022.

42 Source: Bloomberg News, “India Plans Debut Green Bonds to Raise $2 Billion by March,” as of September 29, 2022.

43 Source: Science Based Targets, “Companies committed to cut emissions in line with climate science now represent $38 trillion of global economy,” as of May 12, 2022.

44 Source: J.P. Morgan, Bond Radar. Based on year-to-date issuance as of September 2022.

45 Source: EPFR, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research ESG Credit Monitor. As of September 13, 2022.