The Dollar's Shifting Landscape: From Dominance to Diversification

Assessing Dollar Direction

A decade of US exceptionalism and capital flows

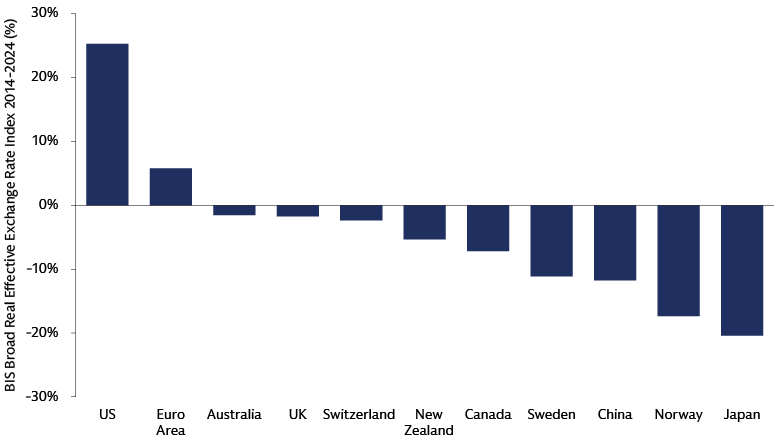

For a decade spanning 2014 to 2024, the US dollar reigned supreme in the currency markets. Its real exchange rate soared by over 25%, leaving other major currencies in its wake. This extraordinary performance was fueled by two reinforcing dynamics.

The first key driver was capital flows propelled by the narrative of US exceptionalism. Over the past decade, global investors have shown a growing preference for US assets, enticed by superior equity returns and higher bond yields. This stood in stark contrast to the persistently low, or even negative, interest rate environment that prevailed in regions such as Europe and Japan. A sustained influx of foreign capital acted as a powerful tailwind, reinforcing the dollar's upward trajectory. This dynamic is reflected in the US balance of payments: a persistent current account deficit—reflecting higher imports than exports—is offset by a capital account surplus, as foreign investors fund both the trade gap and the government’s fiscal shortfall.

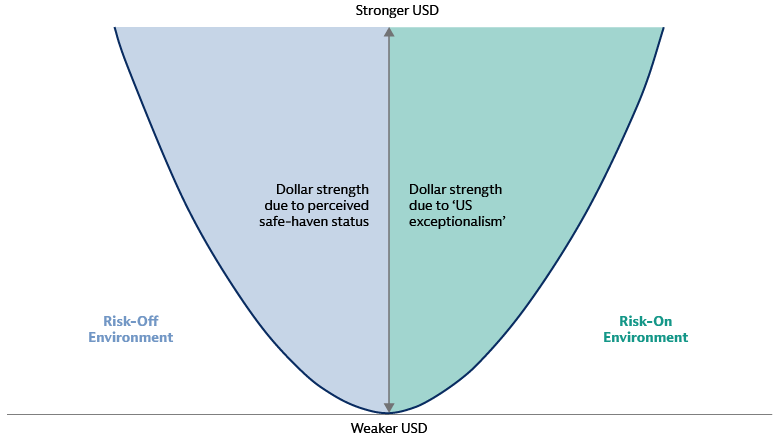

The dollar also consistently benefited from its status as the world's preeminent reserve currency and its perceived role as a safe-haven during times of heightened global uncertainty. This dynamic is captured by the Dollar Smile Theory, popularized by former Morgan Stanley economist Stephen Jen. The Dollar Smile posits that the dollar tends to strengthen under two distinct scenarios: when the US economy thrives (the right side of the smile), driven by rising interest rates and capital inflows, and when global risks escalate (the left side of the smile), fueled by safe-haven demand, even if the US economy itself is faltering. Conversely, the dollar typically weakens when global growth is strong (the middle of the smile). This framework provides a compelling explanation for the dollar's persistent strength over the past decade, supported by both periods of cyclical outperformance and sustained structural demand for safety.

Source: Macrobond, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Goldman Sachs Asset Management. Real effective exchange rates (REER) are derived by adjusting the nominal effective exchange rates by relative consumer prices. As of December 31, 2024.

Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only.

Early 2025: A shift in dollar dynamics?

In early 2025, the dollar began to exhibit uncharacteristic weakness—even during episodes of global risk aversion. This marked a departure from its traditional safe-haven behavior. The initial impetus for this weakness stemmed from improving investment prospects outside the US. The emergence of competitive Chinese AI models, reshaping perceptions of future tech sector leadership, coupled with European fiscal stimulus, particularly in Germany, challenged the "TINA" ("There Is No Alternative") narrative that had previously favored US assets. This shift is reflected in increased fund flows into European assets, resulting in appreciation of the euro against the dollar, reversing the depreciation observed in 2024.

In April, dollar weakness was driven less by the newly announced tariffs as part of the US Administration’s stated goal of reducing the trade deficit, and more by concerns over the perceived uncertainty around the broader tariff strategy.1 The broad and uncertain nature of the reciprocal tariffs unsettled markets and weakened investor confidence in the US as a stable anchor. Additionally, new domestic policies and speculation around a so-called “Mar-a-Lago Accord”—a hypothetical strategy loosely inspired by the 1985 Plaza Accord—may have contributed to recent downward pressure on the US dollar. The idea centers on deliberately weakening the dollar to enhance US export competitiveness. Current US fiscal policy implies sustained large deficits well into the future. As a result, continued recycling of global current account surpluses into US assets—flows that typically support the dollar rather than weaken it—is likely to remain necessary to help contain the cost of financing those deficits.

More recently, dollar softness has shifted from being a broad macro story to a more targeted one—centered on currencies from countries with large positive Net International Investment Positions (NIIPs), such as the Taiwanese dollar and Singapore dollar. These currencies have been historically undervalued due to years of capital recycling: surplus economies have exported goods to the US, earned dollars, and reinvested those dollars into US financial assets. This flow has supported the dollar and suppressed appreciation in their own currencies. Now, that dynamic is beginning to shift. US trade negotiations may be encouraging surplus countries to allow their currencies to appreciate, enhancing US export competitiveness.

Moody’s downgrade of US sovereign debt—from Aaa to Aa1 on May 16, 2025—has renewed focus on the country’s fiscal sustainability. While the decision was largely anticipated, it highlights growing concern over the persistence of substantial budget deficits, even amid solid economic growth and a strong labor market. This backdrop may also be contributing to a more cautious outlook on the US dollar.

This dollar weakness is atypical and contrasts with the 2018–2019 trade war, when the dollar strengthened. During that period, safe-haven flows, strong US growth, Fed tightening, and emerging market stress all supported the dollar.

Catalysts for a sustained downtrend: Regional diversification and rising hedge ratios

Despite the early 2025 weakness, the dollar still appears overvalued based on multiple valuation frameworks. These include purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted for productivity—favored by our Fixed Income team—and the Goldman Sachs Dynamic Equilibrium Exchange Rate (DEER) model, which incorporates long-term fundamentals such as productivity and terms of trade. However, valuation alone rarely triggers currency moves. A sustained downtrend typically requires a macro catalyst—such as a policy pivot, recession, geopolitical shock or reallocation of assets.

Several structural factors could contribute to a gradual rebalancing in global asset allocations. These include persistent concerns over US institutional credibility, elevated concentration in US equity markets, and improving investment opportunities abroad. Together, these dynamics may encourage greater regional diversification—in line with the Embracing a Broader Equity Landscape theme.

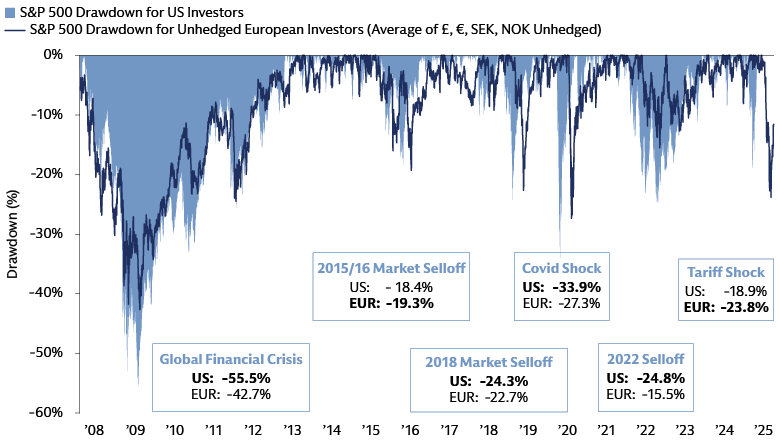

Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Bloomberg. As of May 23, 2025.

Any reallocation is likely to be incremental, in our view. Rather than disorderly divestments of US assets by global investors, a more plausible scenario is a marginal shift in new capital flows—away from the US and toward other regions. This would apply steady, rather than sudden, pressure on the dollar.

Another emerging trend is a rise in currency hedge ratios among large institutional investors. The equity drawdown in early 2025 exposed the risks of unhedged US exposures, as dollar weakness amplified losses for non-US investors Historically, investors relied on the dollar’s safe-haven status and maintained low hedge ratios. In early 2025, however, the dollar’s decline intensified losses on US assets, prompting a reassessment of hedging strategies. Even modest increases in hedging could lead to incremental dollar selling over time.

Change is anything but linear

Despite these pressures, the dollar’s path forward is unlikely to be linear. Several countervailing forces could support the currency in the near term. A relative improvement in US growth prospects could prompt a more hawkish Federal Reserve stance, reinforcing the dollar’s carry advantage. Further de-escalation in trade tensions would also help. Moreover, positive US economic surprises—relative to downside surprises abroad—tend to bolster the dollar.

Positioning also matters. With relatively light active overweight positions in the dollar, there is room for stabilization—or even upside—if sentiment shifts. While real-time data on reserve allocations is limited, fund flow trends offer some insight. European investors have been repatriating capital, reducing US equity exposure in favor of domestic assets. In contrast, non-European investors continue to allocate steadily to US markets, drawn by superior profitability, strong earnings growth, innovation and productivity leadership, robust balance sheets, attractive income potential, and deep market liquidity—attributes we expect to persist. Additionally, companies have announced plans to invest over $2 trillion in the US over multiple years, with foreign governments pledging another $4.2 trillion—signaling sustained inbound investment momentum.2 Overall, we believe it’s too early to call this a structural shift away from US assets. In fact, monetary easing in other markets could further support the dollar’s near-term outlook.

We continue to find the dollar smile a helpful framework for interpreting dollar behavior—where the currency tends to strengthen either during periods of robust US growth or heightened global risk aversion, particularly when the source of uncertainty lies outside the US, which has not been the case so far in 2025. That said, we believe the curve has likely flattened, meaning it now takes more significant shifts in sentiment—either toward optimism or risk aversion—to drive meaningful dollar appreciation.

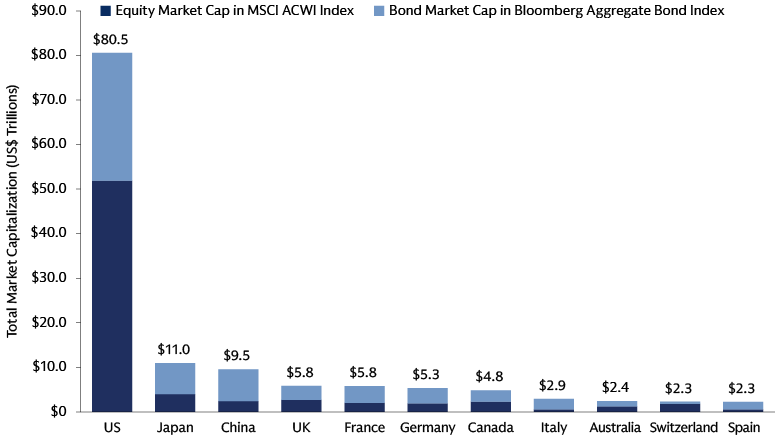

Source: MSCI, Goldman Sachs Investment Strategy Group, Haver Analytics, as of March 14, 2025. This chart demonstrates the Combined Market Cap in Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index and MSCI ACWI Index.

Reserve Currency Status: Resilience Despite Challenges

Historical foundations of dollar dominance

The US dollar’s central role in global finance was cemented by the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement, which established it as the anchor of the international monetary system. Under this framework, other currencies were pegged to the dollar, which was itself convertible to gold. Although the system unraveled in the early 1970s—culminating in President Nixon’s suspension of gold convertibility—the dollar’s dominance endured. The transition to floating exchange rates did little to diminish its appeal, as the dollar’s unmatched liquidity, institutional credibility, and integration into global trade and capital markets continued to attract global demand.

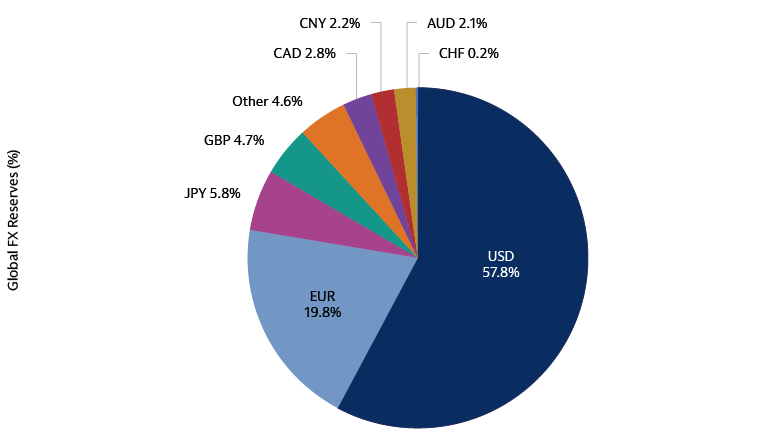

Today, the dollar remains the most widely used currency for trade invoicing, financial transactions and payments, commodity contracts, debt issuance, and foreign exchange transactions. It accounts for approximately 88% of global FX turnover,3 70% of foreign currency debt issuance4 and 58% of official reserves.5 These figures reflect not only the scale and strength of the US economy but also the powerful network effects that reinforce the dollar’s primacy: its widespread use begets further use, embedding it deeply into the infrastructure of global finance.

Emerging challenges

Despite its deeply entrenched role in the global financial system, the US dollar is facing mounting scrutiny. Geopolitical tensions—particularly those linked to the strategic use of US sanctions—have intensified calls for de-dollarization, the process by which countries reduce their reliance on the US dollar in international trade, finance, and foreign exchange reserves. At the same time, growing concerns over domestic policy risks, including rising debt levels, political polarization, and other risks, are prompting investors to reassess the long-term appeal of US assets. Meanwhile, technological advancements such as central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and emerging cross-border payment systems are beginning to offer alternatives to dollar-based transactions. Although these innovations remain in early stages and lack cohesion, they signal the emergence of structural headwinds that could gradually erode the dollar’s dominance over time.

Reviewing the alternatives

Over the past 80 years, numerous currencies and monetary constructs have been proposed as potential challengers—or successors—to the US dollar’s status as the world’s dominant reserve currency. Yet each has ultimately fallen short, constrained by its own limitations and challenges.

- British Pound Sterling: Once the dominant global currency, the pound remained in reserve portfolios after WWII but steadily declined as the US economy outpaced the UK’s. The dollar formally replaced it under the Bretton Woods system.

- Gold: While not a currency, gold was central to the Bretton Woods framework until 1971. Calls for a return to a gold-backed system emerged after the Nixon Shock, but these never gained traction.

- Special Drawing Rights (SDRs): Introduced by the IMF in 1969 as an international reserve asset, SDRs were envisioned as a way to reduce reliance on the dollar. SDRs are not a currency but a claim on freely usable currencies, and their value is based on a basket comprising the US dollar, euro, Chinese renminbi, Japanese yen, and British pound. However, they have remained a marginal tool, limited by their lack of liquidity and practical utility.

- Japanese Yen: During Japan’s economic boom, the yen was seen as a rising contender. However, the bursting of the asset bubble in the early 1990s and subsequent stagnation and deflation curtailed its momentum.

- Deutsche Mark: As West Germany’s economy surged, the Deutsche Mark gained credibility. Its potential was ultimately subsumed into the euro project.

- Euro: Introduced in 1999, the euro emerged as the most serious challenger to the US dollar, gaining traction in global reserves and trade invoicing.6 However, the eurozone debt crisis (2010–2012) exposed structural vulnerabilities—most notably the absence of a fiscal union—that undermined its long-term potential as a reserve currency. Today, the euro accounts for just under 20% of global foreign exchange reserves, still trailing the dollar’s dominant 58% share by a wide margin.7

- Chinese Renminbi (CNY): China’s rapid economic rise and global outreach have fueled efforts to internationalize the renminbi. The currency was added to the IMF’s SDR basket in 2016, and Chinese government bonds were included in major global indices from 2019. Yet despite these milestones, the renminbi still accounts for less than 3% of global reserves,8 constrained by capital controls, regulatory opacity, and concerns over legal and institutional frameworks among other factors.

- BRICS currency proposals: Discussions around a BRICS-backed currency to reduce dollar dependence have surfaced, but these remain speculative and face significant coordination and implementation challenges.

- Digital currencies (e.g., bitcoin): Decentralized digital assets have been floated as potential disruptors to fiat currency dominance. However, their volatility, regulatory uncertainty, and current lack of institutional trust hinder their viability as reserve assets.

- Gold (revisited): In times of geopolitical stress and inflation, gold has re-emerged as a hedge and reserve holdings have been steadily rising. Yet, it remains impractical as a transactional or reserve currency replacement.

- Euro (revisited): The euro’s reserve currency potential has resurfaced in response to Germany’s fiscal expansion and increased defense spending across the region. These developments are expected to drive higher European government bond issuance, including bunds. However, even with this uptick, Europe’s high quality bond market remains significantly smaller and less liquid than the US Treasury market. This persistent structural gap underscores the continued lack of a viable alternative to dollar-denominated assets.

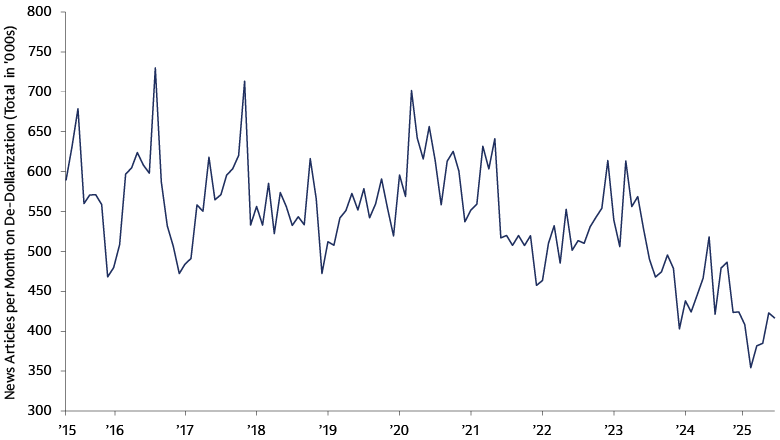

Tracking de-dollarization: More rhetoric than reality

While de-dollarization frequently captures headlines, actual shifts in reserve composition have been modest and incremental. Emerging market central banks have increased gold holdings for diversification and geopolitical hedging, but gold lacks the yield, liquidity and transactional utility of modern reserve assets. Countries like Russia and China have reduced their US Treasury holdings, but global reserves remain overwhelmingly dollar-centric. The dollar still accounts for approximately 58% of global reserves—down from historical highs, but far ahead of any competitor.

Source: Bloomberg, Goldman Sachs Asset Management. As of April 2025. Based on news reports that mention: dedollarization, dedollarisation, de-dollarization or de-dollarisation.

Source: Macrobond, Goldman Sachs Asset Management, IMF COFER data as of Q4 2024.

Outlook and Investment Implications

The starting point is one of broad dollar overvaluation and a significant global overweight to US dollar assets. While the dollar’s dominant role in the global financial system is unlikely to be displaced suddenly, a gradual shift is clearly underway. Both private investors and official reserve managers are steadily diversifying their holdings—driven by concerns over US policy direction as well as improving investment opportunities elsewhere. We believe this trend is expected to continue, contributing to a more multipolar reserve landscape over time.

Rather than a sharp or disorderly retreat from US assets, a more measured rebalancing appears likely—where incremental capital flows are directed toward other regions. This shift may exert steady, albeit modest, downward pressure on the dollar over time.

Importantly, this should not be interpreted as a sign of the dollar’s decline as the global reserve currency. No other currency currently matches the US dollar in terms of scale, liquidity, and institutional credibility. It remains a core strategic asset in global portfolios—serving both as a diversification anchor and a defensive hedge during periods of market stress.

Furthermore, even if the dollar is on a structurally weaker trajectory, the adjustment is unlikely to be linear. We believe episodic rebounds—driven by relative growth differentials, shifts in monetary policy, or geopolitical developments—will continue to create tactical opportunities for active investors.

1 While many investors had anticipated a universal tariff in the range of 10–20% prior to the April 2 announcements, the sweeping scope and seemingly arbitrary application of the measures caught markets off guard.

2 Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research Global Economics Comment: Tracking Inbound US Investment Announcements (May 16, 2025). Some investments may not materialize or may overlap with previously planned US investment, although retrospective examination of similar promises during President Trump’s first term suggests that 80% were realized.

3 Source: BIS Triennial Central Bank Survey conducted in April 2022 and published in October 2022. The latest survey was conducted in April 2025. Preliminary results will be published in September and final results will be published in December 2025

4 Source: BIS Triennial Central Bank Survey conducted in April 2022 and published in October 2022.

5 Source: Macrobond, Goldman Sachs Asset Management, IMF COFER data as of Q4 2024 based on allocated reserves.

6 See European Central Bank, “The International Role of the Euro” As of June 2025.

7 Source: Macrobond, Goldman Sachs Asset Management, IMF COFER data as of Q4 2024 based on allocated reserves.

8 Source: BIS Triennial Central Bank Survey conducted in April 2022 and published in October 2022.