Harnessing Technological Change in Private Markets

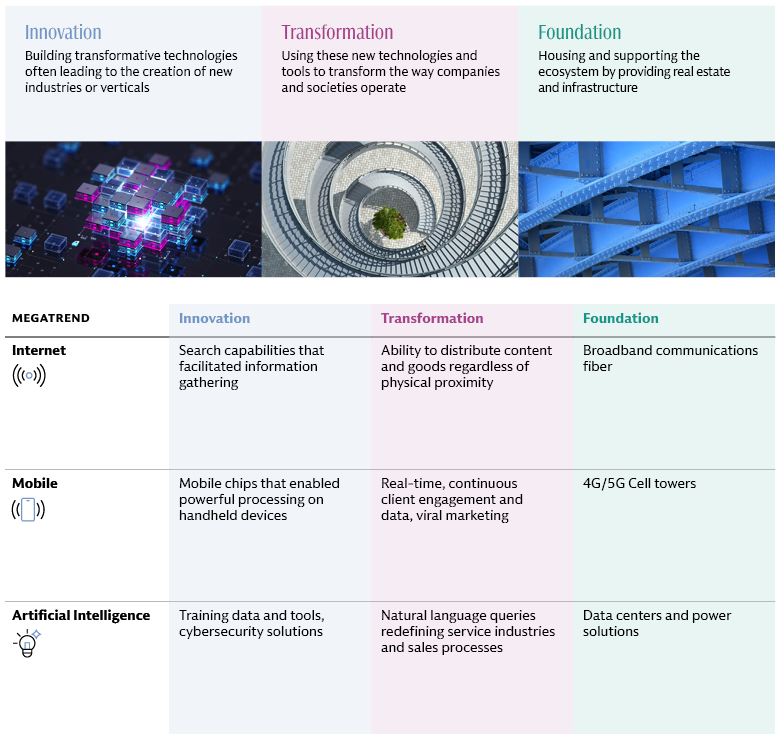

A confluence of megatrends—advances in technology, an international focus on prudent usage of energy and other resources, a changing geopolitical order, and global aging trends—are intersecting to drive rapid changes in the ways societies live, work, and interact. These megatrends are creating waves of technological change and compelling new investment opportunities that can be viewed across three complementary pillars.

Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only.

How Do You Build an Allocation Around a Megatrend?

Building a diversified private markets portfolio centered on innovation may call for a non-traditional construction approach, given the challenges of applying mean-variance optimization to private markets in general and to targeting thematic ideas in particular.

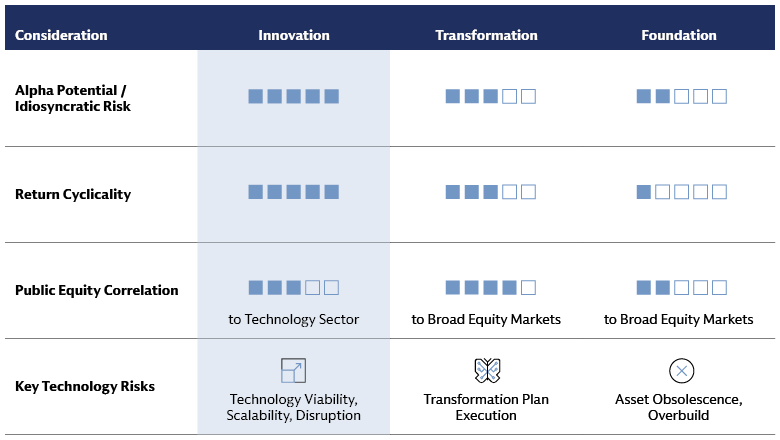

Rather than optimizing across risk/return profiles, the starting point can be allocating across the three pillars. Each pillar aligns with a set of strategies with distinct investment characteristics. Evaluating opportunities based on these characteristics, rather than asset class labels, would result in a portfolio diversified across stages of the technology development cycle, return spectrum, and risk types. The allocation can then be fine-tuned to ensure the portfolio aligns with a desired risk/return profile.

Innovation

This pillar is intuitively associated with venture capital and growth equity, but can also include technology-focused buyouts. Opportunistic real asset strategies that build and develop new properties and infrastructure to house and service evolving technological needs fit into this pillar as well. Although these new assets will ultimately service the ecosystem, their characteristics align with this pillar, in our view.

The underlying companies and assets in this pillar tend to have the fastest growth, the most idiosyncratic return and risk profiles, and, therefore, the greatest alpha potential. This is the case especially for venture capital and opportunistic real assets. Growth equity and technology-focused buyouts have less idiosyncratic risk than the other two strategies, but more sensitivity to public markets – specifically to the technology sector – via valuations and exits timelines.

Key risks are related to technology, albeit in different ways for different strategies. Technology viability and commercialization are a key risk factor at the venture capital stage. In growth equity, risk shifts to scalability and business model viability; in buyouts, to disruption from newer technologies. In opportunistic real asset strategies, a key risk is whether the technology and associated solutions will generate sufficient demand for the service or property being developed. This is the case not only for assets meant to support newer technologies, but also for more established solutions with demand susceptible to rapid technology-driven changes (e.g., trajectory in the efficiency of AI computing processes may impact the trajectory in demand for data center square footage and energy consumption). Long construction times magnify the risk, but build-to-contract can mitigate.

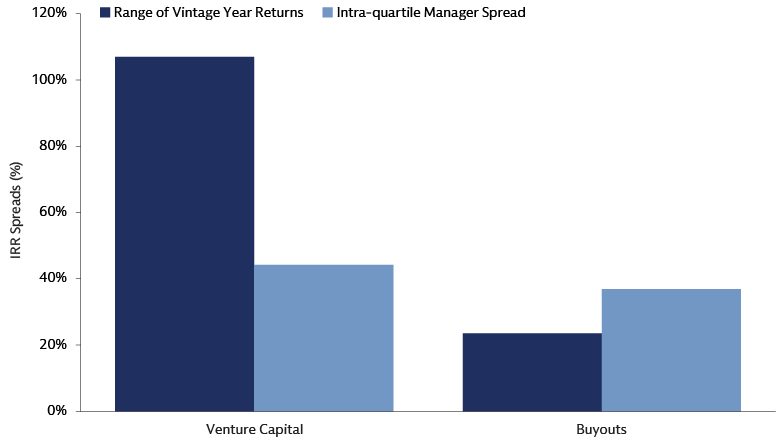

This investment pillar is the most cyclical of the three (especially in venture capital), dependent on being exposed to megatrends at the correct time in the technology development and adoption cycle as well as availability of capital. The internet is a prime example— many ecommerce companies failed in the dot-com bubble, while more-recent iterations enjoy success. Top-quartile funds investing in the vintages around the bubble burst underperformed bottom-quartile funds in more recent vintages.1 Trying to time the market is counterproductive, however. “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen"2 and the length of the commitment and investment cycle in private markets means that attempts at timing the market open the possibility of missing these critical periods. Sizing the pillar and the underlying strategies to account for large potential dispersion across managers and vintages is a better risk management approach, in our view.

Transformation

The long-term focus and governance alignment between key stakeholders inherent in a private ownership structure make it particularly well suited to enacting transformation in a company’s operational trajectory. As such, this pillar of the ecosystem is most closely aligned with transformation-oriented buyout strategies that focus on fundamental value creation via new technologies. The scope is across a wide range of underlying industries, and transformation theses can pivot and evolve over multi-year hold periods – decreasing this pillar’s sensitivity to the technology sector and to the ebb and flow of innovation waves. However, this pillar has more public market beta than the first pillar, insofar as companies are more mature and sensitive to the overall economy, and capital markets inform valuations and exit strategies. This means some macroeconomic cyclicality, but less overall returns cyclicality than in the first pillar.

Execution remains the key driver of returns and key risk factor. Successful execution is predicated on properly accessing the near-term viability of technologies, potential limitations in initial product offerings, capex and operational requirements, and infrastructure capabilities. The ability to successfully integrate new technologies into existing organizational processes and systems is critical to maximize the effectiveness of new technologies and generate an attractive return on capital spend.

Manager-specific factors have driven performance dispersion to a larger extent than macro factors: dispersion between funds in a vintage year has been around 1.5x as much as dispersion of overall industry returns across vintages.3

Source: Cambridge Associates, through Q2 2024. Represents 25 vintage years through 2020 (younger vintages’ performance is not yet meaningful). Range of vintage year returns computed as the difference between the maximum and minimum pooled returns in these vintages. Intra-quartile manager spread calculated as the average of the differences between each vintage year’s top-5% manager and bottom-5% manager. Past performance is not indicative of future returns.

Foundation

This pillar is primarily the purview of real estate and infrastructure. In particular, the focus is on core, core plus, and value-add strategies, which hold existing, fully operational assets that house and provide services to the rest of the ecosystem. Real asset credit strategies fit here as well, including ones dedicated to financing climate transition assets, an emerging area.

The essential nature of the underlying assets and services, combined with limited asset supply due to regulatory or physical constraints, make for sticky customer bases and resilient cash flows. Steady rent revenue makes for an attractive source of income and attractive credit collateral. Regulatory or contractual inflation-tied price escalators for many asset types offers inflation protection. This defensive nature makes this pillar less sensitive not only to economic cycles but, by extension, to macro-driven equity and credit market movements. Underlying asset supply and demand drivers, however, introduce market-, sector-, and asset-specific risk factors.

A key development-related risk in this pillar is obsolescence. Innovation waves have at times led to a disconnect between the assets on the ground and the assets that customers and tenants prefer, with older, “class B/C” office properties a notable recent example. Asset overbuild can likewise render some assets obsolete, if demand does not meet supply in a sensible timeframe. During the dotcom bubble, for example, an ambitious, capex-heavy buildout of fiber networks led to a glut, leading to multiple telecom company bankruptcies but providing cheap distribution capabilities for the next generation’s mobile apps a decade later. Losses in undesired assets are magnified by large capital outlays associated with building, maintaining, and, if necessary, repurposing them, as well as an inability to relocate the asset. An asset can be more resilient if underpinned by a confluence of megatrends. For instance, data center demand is being driven not only by AI but also by mobile usage and the Internet of Things, which is making a wider variety of everyday devices digitally connected. At the portfolio level, resilience can be enhanced by diversifying across sectors and investment themes of underlying positions.

Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only.

Questions To Ask In Manager Evaluation

When selecting managers, it is important to evaluate the suitability of their investment model to the profile of their particular pillar, and their ability to see interconnections across the three pillars of the ecosystem.

Innovation: Is the GP’s investment model a match for their target sectors?

For over two decades, the venture capital model has been largely predicated on capital-light business models and quick development cycles – a good match for software companies. However, it is often a mismatch for capital intensive, longer-development cycle businesses – one reason many early VC cleantech investments failed. Increasingly, the challenges of our world require capex-heavy solutions and/or longer time frames, necessitating an adjustment to the investment model for GPs wishing to pursue these sectors. Some of this is already happening, for instance in life sciences funds. Some innovations, however, may not be suitable to a venture-backed funding model; LPs should evaluate whether the GP has the discipline to avoid such investments.

Transformation: What operational expertise does the GP bring to portfolio companies, and how are they evolving this skillset?

The GP should already have a robust set of resources and expertise to help portfolio companies evolve; the world is moving too fast to build from scratch on-the-go. On the other hand, the GP should continuously enhance and adapt their skillset for recent innovations. Given an increased cost of capital and the front-loaded nature of the costs of transformation, underwriting may need to adapt as well, either planning for extended hold periods over which to benefit from these upfront costs, or finding concrete ways to reap the benefits of transformation faster.

Foundation: How do the GP’s deployment plans align with the potential size of the opportunity set?

Given the defensive nature of this pillar, a key focus is on mitigating downside risk. Real asset GPs need to understand where a megatrend is in the development curve to properly assess where near- and medium-term opportunities will be. Failure in this aspect may be especially costly in this pillar, because the high initial capital outlay may be difficult to recoup if an asset becomes obsolete, unsuitable, or redundant, and the relatively concentrated nature of underlying portfolios mean that a losing investment will have a meaningful impact on the overall portfolio. LPs should evaluate the GP’s approach to estimating the opportunity size, timing, and pricing for an attractive return in their investment thesis, allowing for the possibility of a significant change in either supply or demand. Is the GP quantifying risk accurately? What factors could lead to disruption in contract profiles and therefore the downside protection you are seeking from this area?

Courageous Imagination, Disciplined Risk Management

Technological changes can introduce seismic shifts in the ways in which society functions. Many common aspects of modern life - the ability to communicate through the internet, to shop on the phone, to interact with machines using human language – were impossible a mere thirty-some years ago. But change is never linear, and timelines are easy to misjudge. The beneficiaries of progress may be the trailblazing companies at the forefront, or the subsequent generations that benefit from initial inroads by businesses that were too early or had the wrong model. From an investment perspective, the right blend of courageous imagination and disciplined risk management are critical for success.

1 Cambridge Associates, as of Q2 2024.

2 Attributed to various authors, including Adriaan Schade van Westrum, David Eddings, and Homero Aridjis

3 Cambridge Associates. Data through Q2 2024. Spread of returns between top-5% and bottom-5% managers in each of the past 25 vintages through 2019 were averaged to get the dispersion between funds in a vintage year; spread between the minimum and maximum pooled asset class return across the same 20 vintages was computed to get the dispersion of industry returns across vintages. Vintages 2020 and younger do not yet have meaningful enough results to be included in the analysis.