Private Equity’s New Math - Part 1: A Brief History of Value Creation

Private equity is predicated on active, control-oriented ownership, which allows General Partners (GPs) to reshape acquired companies, their balance sheets, and strategic plans. This approach has enabled the private equity industry to generate 15% internal rates of return (IRR) over the past 10 and 20 years1 —although performance has varied, both across managers and over time, such as around significant transitions in the macroeconomic cycle.

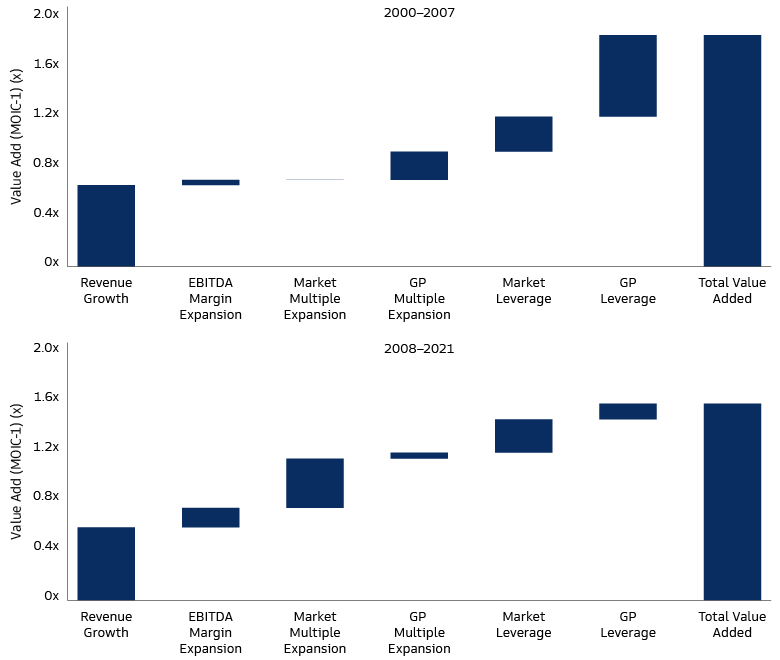

While approaches to executing a buyout investment vary widely, the drivers of return can be broadly classified into four categories: topline growth, margin expansion, multiple expansion, and leverage/financial structuring. Data shows that as the market environment evolved, GPs adapted the private equity playbook to emphasize different levers of value creation depending on market conditions. Leverage and financial structuring have become less important in recent decades, for example, while multiple expansion and operational factors have gained prominence. At today’s inflection points in the economy and global markets, we believe the playbook will evolve once again. By understanding how the value creation model has evolved in light of changes in the broader market context, we can make inferences about the next stage of evolution necessary for private equity to continue generating alpha for investors.

The Early Days: Leaning on Leverage

The buyout industry as we know it today began to coalesce in the 1980s,2 when tailwinds from tax and regulatory changes, combined with the development of leveraged loans, led to the advent of the “leveraged buyout” (LBO). The term itself suggests that leverage is a key component of the strategy—and in fact, leverage was the primary driver of returns in those early days. Much of the value creation thesis for the equity owner was predicated on changing the portfolio’s capital structure towards a higher debt/value ratio.

With valuations structurally low and debt readily accessible up to 5x EBITDA, GPs could finance as much as 90% of the overall purchase price with debt and generate attractive returns on their equity investment even with little growth at the overall company level.3

This value creation model lent itself to a very specific investment selection and operating strategy. With high leverage acting as the primary value creation driver, buyouts in this era generally focused on acquiring “cash cow” businesses and aggressively slashing costs to maximize cash flows for debt repayment. In many cases, the underlying companies had been operating inefficiently, making cost savings a straightforward endeavor. Breaking up the acquired business and selling the underlying assets to help pay down debt was another commonly used strategy.

However, such an aggressive leverage structure left little room for operational stumbles. Relatively small declines in revenue growth or margins (e.g., flat nominal revenues and 1% annualized margin declines) at the enterprise level could wipe out the entire equity investment. A number of prominent LBO-owned businesses went bankrupt in 1990-1992. A 1993 study showed that among the 83 large LBOs completed between 1985 and 1989, 26 defaulted and 18 entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings.4 The dotcom boom and bust of the late-1990s marked the end of the first era of leveraged buyouts.

Second Era: Fundamentals in Focus

In the next era, between the dot-com bust and the global financial crisis (GFC), private equity began its evolution to the industry of today. GPs pursued a more prudent capital structure. At the same time, post-GFC regulations effectively capped senior leverage issuance at 6x EBITDA while equity valuations moved structurally higher. In recent years, equity contributions have made up as much as half of the overall financing in LBO transactions.

Against this market backdrop, GPs’ value creation strategy shifted towards generating greater value at the enterprise level. Focus turned to driving revenue growth and margin expansion – unlocking untapped potential in underperforming businesses, fine-tuning operations of healthier companies, and building scale through add-on acquisitions. Some private equity firms began hiring dedicated operating professionals to work alongside their portfolio companies’ management teams to unlock value. Private equity managers were able to professionalize and improve their companies, making necessary changes away from the short-term focus of the quarterly earnings cycle and with a governance structure that closely aligns owners and management teams. As a result of these efforts, private equity managers have been able to generate superior operating performance in their portfolio companies, in aggregate, than was experienced in public markets.5 This, in turn, made them more attractive partners to management teams. Revenue growth has been the most persistent source of value creation since 2000—contributing more than one-third to overall value-add. 6

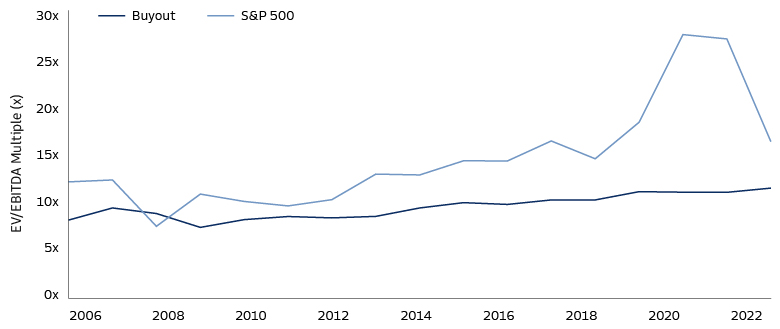

Data also shows that over the past two decades, PE-owned companies experienced similar levels of revenue growth across sectors, even though the underlying sectors have had fundamentally different growth profiles.7 This finding may reflect a strategic approach by private equity managers to drive the growth necessary to achieve investor return targets. While earnings growth ultimately drives value creation in equity markets, achieving it calls for a certain minimum threshold of topline growth. Private equity managers sought to achieve it through a combination of capturing broader economic tailwinds and leveraging operational skill, depending on the prevailing market environment. Prior to the GFC, when overall market-level revenue growth was higher than in the more recent past, sectors that tend to experience more moderate growth (e.g., consumer staples and industrials) provided sufficient baseline growth for buyout investors. But in the last decade, as economy-wide corporate revenue growth slowed, GPs turned to intrinsically higher-growth sectors. One example is information technology, where secular demand tailwinds and the broad evolution of the software industry to a software-as-a-service (SaaS) model have made for more consistent cash flows and robust margins. These features made software companies eligible candidates for a leveraged buyout investment model. Another example is healthcare, where fragmented markets were conducive to the buy-and-build strategy, while aging global populations, evolving modes of care delivery, and advancements in life sciences present attractive structural opportunities for growth. A shift to higher-growth, higher-valuation sectors such as IT and healthcare has contributed to a steady rise in private equity purchase-price multiples paid. However, private equity multiples have remained below those of public markets, which have been driven by the largest companies in the indices—increasingly, by large technology companies.

Source: Refinitiv. As of December 31, 2022.

Despite a focus on improving operational efficiency, over the past two decades private equity firms have struggled to achieve significant margin expansion in their portfolio companies. In part this may be a function of the broad professionalization of corporate management in this time frame. With companies operating more efficiently at acquisition, compared to the case in the 1980s, further efficiency gains are more challenging to achieve.

Post-Crisis: Riding the Beta Wave

Multiple expansion has also served as in important contributor to overall buyout value creation in the past 20 years, particularly since the GFC. Buyout data suggests that fully exited deals initiated in the period between the dot-com and GFC recessions (2000-2007) experienced multiple expansion of 0.2-0.5x per year, which has risen to ~0.5-1x since the GFC (i.e., 2-4x turns of EBITDA over the life of the deal).8 This multiple expansion has come through a combination of market-based (beta) effects and GP-specific (alpha) effects, such as improved quality and growth prospects of the companies from acquisition to exit due to the GP’s active involvement in company transformation. Another effect has been evidenced in the frequently employed buy-and-build (platform) strategies, wherein the manager combines a portfolio company with multiple smaller companies in the same business line. Because smaller companies tend to transact at lower valuations, this strategy averages down the cost basis for the consolidated enterprise, and has helped to keep purchase-price multiples well below public market valuations.

Another factor that has enabled private equity GPs to generate excess multiple expansion is a carefully considered exit strategy. As a control investor, a manager can time exits based not only on the strength of the overall market environment but also on the dynamics of the potential buyer universe for their particular company. Managers can closely study the company’s industry and the activity of potential buyers, to set the exit strategy. Along with reshaping the company’s operations, they can reshape the narrative of the company, framing it with the specific buyer universe in mind.

Academic analyses attribute the multiple expansion in the period between the dotcom crash and the GFC primarily to the effects of GPs’ efforts. Conversely, the analyses suggest that multiple expansion since the GFC has been attributable primarily to market-based effects (given the significant run-up in public company multiples during this period), accounting for a quarter of overall value created for buyout deals executed since 2008.9 Nevertheless, GP-based multiple expansion added value in this period as well; buyout exit multiples being consistently above acquisition multiples in a given year serve as evidence of alpha effects.10

Source: Matteo Binfare, Gregory Brown, Andra Ghent, Wendy Hu, Christian Lundblad, Richard Maxwell, Shawn Munday, and Lu Yi, “Performance Analysis and Attribution with Alternative Investments.” As of January 24, 2022.

While multiple expansion played a meaningful role in value enhancement at the industry level over the past decade, our model suggests that it alone was insufficient to generate above-median private equity returns. An investment structured on industry-average terms that experienced a 2.5x multiple expansion would have generated around a 1.5x net TVPI (Total Value to Paid-in Capital) / 11.5% net IRR (Internal Rate of Return) from multiple expansion and leverage alone (without generating any revenue growth or margin enhancement). This would put the deal in around the third quartile of fund returns. To achieve a net TVPI of 2.0x (the approximate result of a 2.5x gross TVPI) and move into the top half of performers, for example, the GP would also need to generate a 7% annual revenue growth rate—above the level experienced by publicly traded U.S. companies in the 2010s.11

Uncharted Territory: The Road Ahead

We believe the next ten years are unlikely to look like the last ten. Investors are facing a vastly different backdrop than the relatively benign, supportive environment of the post-GFC to pandemic era. GDP growth is expected to slow, or potentially enter recessionary territory, in many parts of the world. Inflation is expected to be structurally higher, likely leading to higher steady-state interest rates than was the case in the past decade. This will elevate the cost of capital for both public and private companies – a phenomenon that many investors and managers are experiencing for the first time in their careers. Many market strategists are anticipating these dynamics to weigh on asset performance, yet investors will likely demand higher returns (if anything) from their private markets portfolios, with an elevated risk-free rate setting a higher bar for all asset returns—particularly in asset classes viewed as being more complex.

In our view, the radically altered investment backdrop means that for private equity, the path to operational value creation will need to look different than may have been the case in the past. Leverage and multiple expansion are unlikely to add as much to value creation as they have in the past. GPs, and many LPs, are coming to the realization that operational value creation levers will become even greater determinants of success or failure for individual deals and funds.

In the next article of this series, we will delve deeper into different value creation strategies and their implications for private equity investing.

1 Source: Cambridge Associates. Pooled buyout IRRs over 10-year and 20-year periods through 4Q 2022.

2 Source: “Private equity, history and further development,” Harvard University. As of December 27, 2008.

3 Source: Prof. Gregory Brown, IPC. “Debt and Leverage in Private Equity: A Survey of Existing Results and New Findings.” As of Jan 4, 2021.

4 Source: Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol 19 No 4. “Private Equity: Boom and Bust?” As of fall 2007

5 Source: Cambridge Associates LLC Private Investments Database, FactSet Research Systems, and Frank Russell Company. Data from January 1, 2000 – March 31, 2022.

6 Matteo Binfare, Gregory Brown, Andra Ghent, Wendy Hu, Christian Lundblad, Richard Maxwell, Shawn Munday, and Lu Yi, “Performance Analysis and Attribution with Alternative Investments.” As of January 24, 2022.

7 Source: Prof. Gregory Brown, IPC. “Debt and Leverage in Private Equity: A Survey of Existing Results and New Findings.” As of Jan 4, 2021.

8 Source: Prof. Gregory Brown, IPC. “Debt and Leverage in Private Equity: A Survey of Existing Results and New Findings.” As of Jan 4, 2021.

9 Matteo Binfare, Gregory Brown, Andra Ghent, Wendy Hu, Christian Lundblad, Richard Maxwell, Shawn Munday, and Lu Yi, “Performance Analysis and Attribution with Alternative Investments.” As of January 24, 2022.

10 Burgiss Company Fundamentals Review. As of 4Q 2022.

11 Based on S&P 500 aggregate revenue annual growth rates as reported by Dr. Edward Yardeni: “Corporate Finance Briefing: S&P 500 Revenues & Earnings Growth Rate.” As of May 29, 2023.