Demographics: The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly

The French philosopher Auguste Comte is often quoted by the economic community as saying, “Demography is destiny.” We believe he was wrong. Demographics are just one factor influencing economic and social outcomes across countries, but it can play a critical role in shaping public policy, inflation and investment decisions over long-run time horizons. This article addresses the many effects of the most important demographic trends, looking at the macro implications, how countries adapt policies to changing populations, and critically, what that means for investors.

Demographics: An Overview

Any significant change in the population—for example, average age, dependency ratios, life expectancy or birth rates—can have material implications for an economy. Demographic change can influence the underlying growth rate of an economy, structural productivity growth, living standards, savings rates, consumption and investment. It can influence the long‐run unemployment rate and equilibrium interest rate, housing market trends and the demand for financial assets. Economies with rapidly expanding prime-age population cohorts (ages 25-54) enjoy the benefits of improved potential gross domestic product (GDP) growth, but also face the challenge of creating sufficient employment to satisfy the needs and desires of that population. By contrast, aging societies typically must wrestle with the reduction of their labor force and rebalance their economies to devote a much higher share of national income to social and health care (irrespective of whether that is publicly or privately financed). The challenges vary according to the dynamics and parameters of the population pyramid. In many cases, the questions are both absolute and distributional; both types of questions matter for investors seeking to allocate capital efficiently.

These questions have immediate practical importance. A number of the world’s major economies are in the midst of the most rapid demographic change since World War II, with the potential to reshape the macro and investment landscape for decades to come. In the US, declining fertility rates and an aging population are not as much of a challenge as in other countries, yet the labor force participation rate is at multi-decade lows—a secular trend that has been catalyzed by the exogenous shock to the labor market created by COVID-19 lockdowns.

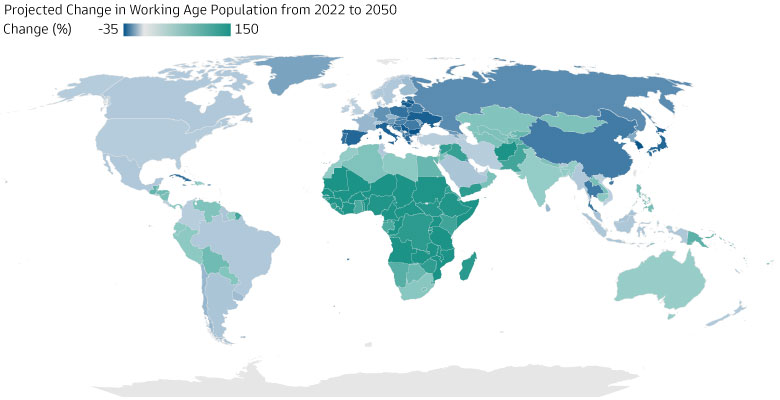

By contrast, China faces a Lewis Turning Point1 as its surplus labor disappears while the aging population grows—a combination that could fundamentally redefine the contours of the world’s second-largest economy with potential global consequences. Put simply, demographics strongly suggest weaker trend growth in China over the years ahead. Nor is China alone in facing that kind of demographic pressure; Germany, Italy and large parts of Eastern Europe may need to confront the implications of shrinking labor forces as the baby boom generation retires.

Conversely, many emerging-market economies have much more positive demographic profiles. For example, India recently overtook China as the most populous country in the world, and its youthful profile will yield a demographic dividend for decades to come.2

Source: United Nations, Haver Analytics and Goldman Sachs Asset Management. As of June 17, 2023. The economic and market forecasts presented herein are for informational purposes as of the date of this presentation. There can be no assurance that the forecasts will be achieved. For illustrative purposes only.

Why Demographics Matter: A Macroeconomic Perspective

Measuring the impact of population aging on economic growth can be complex and multi-faceted. Any meaningful economic analysis may benefit from considering demographics in conjunction with other long-term trends like the increased development and adoption of artificial intelligence (AI), efforts by governments to decarbonize, and the fracturing of the global economy.

Other factors being equal, less favorable demographic impulses suggest potential growth will be weaker. This is primarily a function of a shrinking labor contribution. For example, the US Congressional Budget Office estimates increased female participation rates and the emergence of the baby boom generation combined to have added approximately 1.7 percentage points per year to average growth in US potential real GDP growth from 1948 to 2001.3 As the population ages, the size of the working-age population tends to decrease. This can lead to a decline in the labor force and potentially lower economic output.

But demographics can also impact other components of potential growth beyond labor market volumes (headcount). The aging of the workforce could also depress investment, thus having a negative impact on capital formation. For instance, older workers may draw down investment assets to pay for expenses as they near retirement, or they may pivot to fixed income or cash as their risk profile becomes more conservative with age. Older individuals tend to have greater healthcare needs that can increase healthcare expenditures. A shift in expenditures to healthcare from sectors with higher productivity might potentially reduce overall productivity and affect growth as a result.

For a variety of reasons, the statistical relationship between the aging of the workforce and productivity is believed to be hump-shaped, albeit with factors such as health and education levels contributing to variations in peak productivity.

Aging and AI

The aging of many economies coincides with the increasingly widespread adoption of generative AI, which may go some way to supporting productivity at the aggregate level. Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research (GIR) estimates that generative AI could—depending on its capability and adoption timeline—raise annual US labor productivity growth by just under 1.5 percentage points over a 10-year period following widespread adoption.4 This could eventually increase annual global GDP by 7%.

While AI could be the next driver of GDP, it is unclear how workers of varying age, skills and economies will be affected by potential displacement, particularly in fields including customer and legal services, coding and content creation.

Thus while demographics could have a significant negative impact on economic growth rates in many major economies—taking into account how aging societies may spur innovation—the conclusions are more complex and nuanced.

Inflation

The net impact of aging on inflation depends on the relative strength of a number of cross-currents. We believe aggregate nominal demand will probably decline (a disinflationary effect) as a rising share of the population retires (and income levels typically decline), but aggregate supply will also fall (an inflationary effect) as the labor force diminishes in size. Given that (full) retirement is a complete cessation of economic production, but retirees will only partially (if at all) reduce their demand, the net impact of these two high-level forces is likely to be inflationary.

The aggregate data may not tell the full story, however; shifts in spending patterns at the regional or sector level can be equally powerful. For example, if aging societies display differentiated spending patterns, this can mean expenditure is redirected toward sectors where there is existing supply-side capacity to absorb it, in which case the inflationary impact is dampened considerably. Micro (sector-level) may be as important as macro (broad-economy) trends.

Similarly, one of the economic lessons from the post-COVID reopening is that sector-level labor market dislocations (whether surfeits or shortfalls) from structural breaks can have major impacts on wage dynamics. Careful micro-econometric analysis may be required on a case-by-case basis, rather than overarching grand pronouncements. And just as when considering the impact of aging on growth, so too with inflation it is important to consider other contemporaneous structural changes. For example, technology and the wide adoption of AI may provide significant disinflationary forces across many economies, but with uncertain impacts on the capacity (and therefore inflationary consequences) for health and social care that are likely to see higher demand in aging societies.

Implications for Policy

Critically, the impact of an aging population on economic growth and inflation can vary across countries and depends on factors such as government policies, labor market dynamics and healthcare systems. Policymakers can adjust immigration policies, labor market regulations, and investments in healthcare and education to address the challenges posed by an aging population and promote sustainable long-term economic growth. That said, with China—one of the major sources of labor supply for the past 20 years—also suffering from deteriorating demographics, advanced economies may start to struggle to import labor from such places either via migration or outsourcing of production.

Overall, we think that population aging across most developed markets and China will largely be inflationary, especially when coupled with decarbonization and deglobalization. That will potentially create a profoundly different inflation dynamic for central banks to contend with relative to the past 15 years. Demographics point to structural stickiness to inflation, suggesting higher nominal policy rates in the decades ahead. This would be a reversal from the post-Global Financial Crisis era of low inflation and policy rates stuck at the effective lower bound, with possibly far-reaching consequences for fixed income investors.

An aging and longer-lived population also creates fiscal challenges around health and social care and the financing of state pensions. Those challenges are exacerbated when—as is the case for many developed markets—they come with a decline in fertility rates. On a neutral assumption of broadly unchanged net migration flows, one of the many consequences of those demographic dynamics is to raise questions about the sustainability of public pension provisions on existing parameters such as retirement age, contributions, payouts and payment protections. For example, in the UK, where demographics are not particularly adverse, the Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that the cost of state pension provision will rise from 4.8% of GDP currently to 8.1% by 2070.5

Policymakers and the broader community of stakeholders may need to debate whether those costs are socially acceptable, or if there could be a need for a reappraisal of the appropriate levels of provision. Such debates will not be purely technocratic or take place against a sterile backdrop, as the recent French demonstrations against an increase in the retirement age illustrate.6 These are vital questions that touch on fundamental elements of the social contract. What is the appropriate level of entitlement that citizens can expect to access? At what age? What level of taxation is required to finance that? And what sort of immigration policy is needed to meet those requirements?

Portfolio Construction

Just as the economic impact of demographics has the potential to be significant, so too may be the investment consequences. For long-term investors who are looking to build robust portfolios beyond a single economic cycle, population dynamics play an important role. While no investor can accurately predict what the coming decades have in store for financial markets, understanding the implications of aging demographics for markets can help investors make more informed investment decisions and build better portfolios.

One asset class that may be more easily linked to demographics is real estate.7 Housing demand depends on the age structure of a society and on residential population trends. The demand for residential property is therefore more directly affected by demographic changes than in many other markets. As residents age, the average household size shrinks so more apartments are needed per capita. We think this may benefit certain sectors such as senior living facilities. On the other hand, a shrinking population can be negative for the housing market because empty buildings are typically not pulled down. While according to the United Nations the global population is expected to grow over the next 60 years, some countries like Japan—whose population is in decline—may face structural housing challenges. Infrastructure could also be transformed to support the needs of aging populations including roads, waste management and digital technology.

By contrast, the impact of demographics on other financial assets is sometimes less clear-cut. According to a 2016 study from the San Francisco Fed, the main channel through which demographics affect real interest rates is the increase in life expectancy.8 Rising life expectancy tends to be associated with lower interest rates because people save more in anticipation of a longer retirement period. In principle, as the global population becomes older, one can expect interest rates to be lower in the long run. That said, the age structure may also capture the persistent component of interest rates. Recent dynamics point to potentially higher yields over the next decade, which is consistent with an environment of higher inflation.

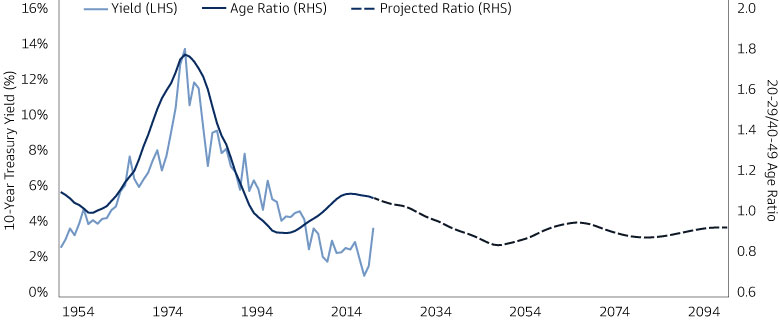

We believe the composition of the population matters too, especially that of the working age cohort, as suggested by a 2015 paper from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).9 The ratio of people aged 20-29 and 40-49 shows a statistically significant relationship with the 10-year nominal government bond yield in the US. While many other factors are at play, the regression analysis suggests a strong relationship between the two.10 And this mostly holds true when applied internationally.11 People tend to borrow when young, invest for retirement and their children’s college when middle-aged, and live off their investments once they are retired. All else equal, prevailing long-term nominal government bond yields in advanced economies will therefore bear some relation to the balance between the young, who are the spenders, and the middle-aged, who are the savers. When the ratio between those two cohorts is high, there will be excess demand for consumption by the younger population. This tends to reduce the demand for bonds, pushing yields higher and encouraging saving by the middle-aged cohort. By contrast, when the ratio is low, there will be excess demand for saving by the middle-aged population, which may push up the price for bonds, potentially prompting yields to fall.

Source: United Nations and Goldman Sachs Asset Management. As of June 12, 2023. The economic and market forecasts presented herein are for informational purposes as of the date of this presentation. There can be no assurance that the forecasts will be achieved. Past performance does not predict future returns and does not guarantee future results, which may vary. For illustrative purposes only.

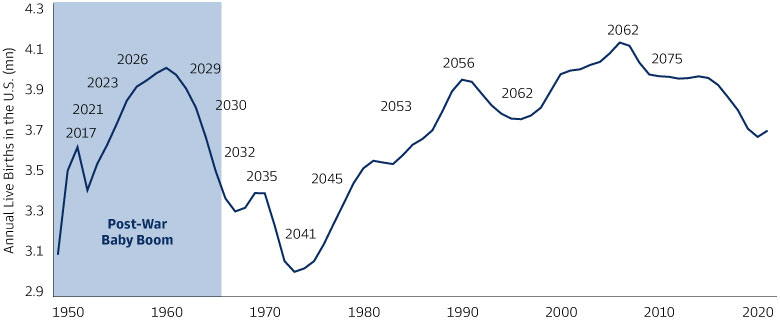

This ratio changes over time, as different age cohorts work their way through the population structure. In the US, the ratio has recently grown as baby boomers—people born between 1946 and 1964—are starting to retire, pointing to potentially higher long-term yields over the next 10-15 years. Beyond that, the ratio of people aged 20-29 and 40-49 in the US could put some downward pressure on the 10-year Treasury yield by 2050, but rates could rise again in the second half of the century as millennials—born between 1981 and 1996— retire.

Source: United Nations and Goldman Sachs Asset Management. As of June 14, 2023. The year they turn 65 marked on top of the line. The economic and market forecasts presented herein are for informational purposes as of the date of this presentation. There can be no assurance that the forecasts will be achieved. Past performance does not predict future returns and does not guarantee future results, which may vary. For illustrative purposes only.

For equities, there tends to be an inverse relationship between the equity risk premium (ERP) and the prevailing level of interest rates, because the ERP is defined as the difference between the expected return on stocks and the estimated expected return on risk-free bonds. Therefore, we expect the ERP to follow a similar, albeit opposite, pattern to bond yields. In other words, in the US at least, the ERP is likely to fall in the next 10-15 years as yields rise and fixed income challenges equities as an attractive investment alternative. Beyond that time horizon, the ERP may increase until 2050 as yields fall, and decline again in the second half of the century as yields trend upward. This will likely vary from country to country.

A dwindling workforce could also potentially weigh on equity valuations. Simply put, companies require economic growth to prosper, and an increase in the working-age population contributes directly to that growth. If the working-age cohort is shrinking, stagnation may set in, and firms will have a harder time growing their revenues and earnings.

But demographic change may also present potentially attractive investment opportunities. For example, companies that provide healthcare services to the elderly or those that can adapt to these new consumption trends are likely to benefit. Also, the expected reduction in labor supply may accelerate the adoption of new technologies such as AI. Firms that enable these technologies and help other companies adopt them effectively may profit from this. We see opportunities in venture capital or growth equity which can capture this trend early.

Overall, portfolios may have to be built differently in the future. Over the next 10-15 years, higher yields and lower equity risk premia across developed markets might prevail, but beyond that, much is likely to depend on the evolution of the relationship between the young and the middle-aged at the time, which in turn may potentially hinge on economic policies and migration trends. For example, raising the retirement age could change the balance between spenders and savers, while raising inflation targets to acknowledge the potential inflationary impact of deteriorating demographics may have profound implications for portfolio construction. (We explored a scenario of higher inflation regime in Is 3% the New 2%?).

Countries with relatively similar magnitudes of aging may also have different asset price dynamics. Furthermore, companies that offer products, services and technologies that are materially and beneficially exposed to the dynamics of consumer spending behavior could present attractive long-term investments. Finally, many emerging economies have more positive demographic profiles than advanced economies, and therefore may offer attractive diversification opportunities for investors exposed to aging population dynamics. Therefore, we believe portfolios should be constructed with these trends in mind.

1 A Lewis Turning Point is a situation in economic development where a surplus of low-cost labor is fully absorbed, leaving a shortage of workers. This may in turn push up wages, consumption and inflation rates.

2 United Nations. As of April 24, 2023.

3 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, “Labor Force Participation and the Prospects for U.S. Growth.” As of November 2, 2007.

4 Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, “The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth.” As of March 23, 2023.

5 UK Office for Budget Responsibility, “Fiscal risks and sustainability – CP 702.” As of July 2022.

6 Financial Times, “France hit by more protests against pension reform.” As of April 6 2023.

7 Gevorgyan, K. (2019). Do demographic changes affect house prices? Journal of Demographic Economics, 85(4), 305-320.

8 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, “Demographics and Real Interest Rates: Inspecting the Mechanism.” As of March 2016

9 International Monetary Fund, “Demographics and The Behavior of Interest Rates*.” As of June 2015.

10 Goldman Sachs Asset Management. As of June 2023.

11 International Monetary Fund, “Demographics and The Behavior of Interest Rates*.” As of June 2015.