The Private Markets Allocation Conundrum

The Dreaded Denominator

For many investors, private market asset allocations have come into focus, with both sides of the equation being impacted. Now with public markets experiencing drastic swings for a variety of reasons, observed portfolio allocations are being altered. But private asset marks are smoothed: adjusted quarterly and based mainly on changes in fundamental operating performance rather than on gyrating market sentiment. These features of private markets tend to mute overall portfolio volatility. Since 2000, buyout funds have trailed public markets in 32 of the 39 quarters when the MSCI ACWI was up 5% or more. Conversely, buyout funds have outperformed in 30 of 31 of the quarters in which the MSCI ACWI was negative over that period.

As a result, investors can become mechanically over/underweight to private markets during bouts of public market volatility. Known as the “denominator effect,” 1 this dynamic can be exacerbated by the lagged nature private market performance reporting (i.e., reported public valuations reflect the most up-to-date values, reported private valuations reflect NAVs typically one to three quarters earlier). The COVID-era denominator effect was intense but short-lived, as public markets recovered quickly and strongly; now with markets seeing drastic movements, discussions of the denominator effect have returned. The recent dearth of distributions is amplifying the imbalance with a “numerator effect.” As a result, some LPs have considered pulling back new private market commitments to stay within allocation ranges. But reacting to transient market moves can be counterproductive, as exhibited with the whipsawing movements in recent weeks.

Keep Calm and Commit On

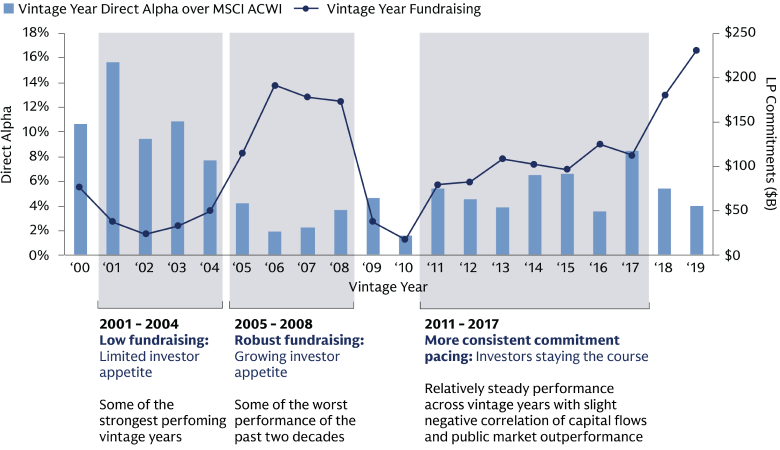

Many investors encounter issues by implicitly working towards a cash-flow neutral private markets strategy in any given year, with distributions supplying the liquidity need to meet new capital commitments. The problem with this approach is that is a pro-cyclical strategy: investors will be less likely to deploy capital in downturns when distributions dry up and the denominator effect kicks in, and more likely to deploy at market peaks when distributions tend to be strong. Fund performance, on the other hand, has been countercyclical, with better-performing vintages emerging during market pullbacks while broad performance has lagged for funds deploying when transaction activity and valuations are highest. Investors that pulled back following the dotcom bust or GFC would have missed out on relatively strong performing vintages.

Cambridge Associates, as of Q3 2024. Past performance does not predict future returns. Capitalization represents the capitalization of funds reporting to the Cambridge Associates database for each vintage year. Vintages 2019 and younger are too young to show meaningful performance results.

Experienced investors understand that private markets are intended to be a long-term asset class, not one that can be timed. Value creation efforts take time but can be achieved regardless of the market backdrop through management uplift, technology adoption, and inorganic growth. For many investors, private equity can help to diversify away from the large-cap, concentrated nature of public markets, while potentially mitigating some of the risks of small- and mid-cap exposure through the active ownership model and control premium. We believe that private equity managers not only are better able to enact operational value creation, but also to capture those gains via exit events that establish a suitable clearing price, as opposed to public equities where pricing can be dislocated from fundamentals for an extended period. When the market backdrop is not conducive to sales, capable operators are able to continue to compound sales and revenue growth to put the asset on a solid trajectory for when capital market activity revives. And if fundamentals are strong but sellers are not pleased with current bids, there are increasing options for partial exits via the secondary market and structured liquidity solutions.

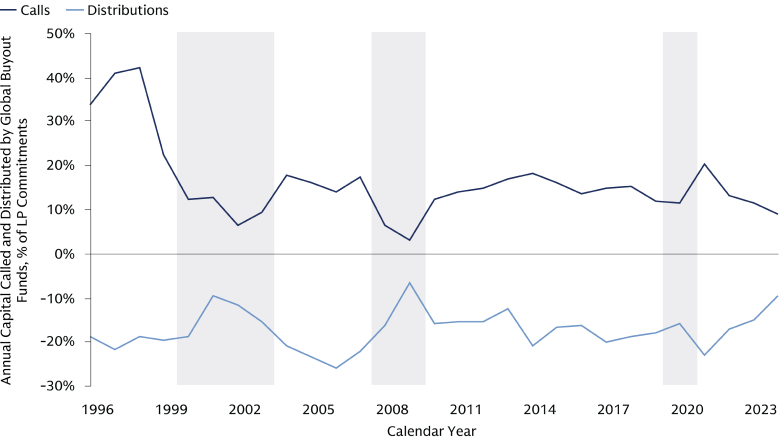

Strategy around entry and exit timing should be the purview of fund managers executing individual deals, whereas private market commitments are not structured to be traded; capital is committed upfront but deployed over several years, so investors need to already have commitments in the ground to take advantage of market dislocations today. For fund managers with dry powder on hand, extended drawdowns can provide opportunities to acquire and recapitalize high-quality assets at attractive prices. To that end, we believe a consistent program of annual commitments could result in better performance through market cycles and allow investors to stay on a track towards target allocations. Today, sophisticated approaches and tools are available that allow for such an approach, customizing across asset classes, fee structures, and other variables. Conversely, altering commitment pacing schedules year by year can lead to under/overshooting an allocation, potentially forcing investors to further alter their strategy to come in line with targets. Cash flows can also gyrate when commitment pacing is altered, introducing a cash drag and/or limiting the ability for the program to be self-funded. Importantly, as private market allocations expand into new asset classes, potential allocation and liquidity issues will vary. In private credit, for example, distribution rates have remained relatively resilient compared to both private equity and real estate, helping to mitigate the numerator effect.

In setting their commitment strategy, investors should be considering the long-term trendline of portfolio allocations rather than specific levels on a given day or week. For changes in commitment pacing to be prudent, they need to be informed by a belief that the long-term trajectory of the overall portfolio has changed, such that the value of the corpus will be meaningfully different in the longer term. This would result in changes to the target for the absolute value of the private market, requiring assumptions about commitment pacing dollars to be revisited.

Solving for the Denominator Effect

How do investors solve for the denominator effect, enabling consistent commitments over the market cycle while staying close to target allocation? The first step for investors is to assess their approach to private market allocation targets. Establish ranges for target allocations that insulate the portfolio from day-to-day public market gyrations. When an allocation threshold is breached, allowing a grace period of a few quarters can help to address short-term market fluctuations and provide sufficient time to assess potential approaches if the allocation does not come back within range. Some investors have already learned this lesson during the GFC and implemented these changes in their governance structures, which helped them to weather the COVID-era market drawdown and volatility. To be prepared for contingencies, investors estimate how much of public market returns their private markets may capture on an accounting basis, as well as some reasonable stress scenarios of how much portfolio value may fluctuate in the near term. A stress test can also estimate cash flows, recognizing that contributions and distributions tend to move together.

Cambridge Associates, as of September 2024. Data for buyout funds. Capital called represents the average called across funds that were 1-4 years old in a given calendar year. Distributions represents the average capital distributed across funds that were 7-13 years old in a given calendar year. Shaded boxes represent the dot-com bust, the global financial crisis, and the COVID period.

When investors need to change course in private markets, different access points and fund structures may be helpful. Co-investments are one tool that can be adjusted more nimbly than fund commitments, because there isn’t the same lag between commitment and deployment. However, investors need to consider sizing and concentration implications. We also acknowledge that paring back co-investments may increase the total cost of the program for large institutions who get fee breaks on co-investments. Evergreen funds are another option to navigate liquidity and allocation challenges. These vehicles can complement drawdown funds, with their evergreen nature providing flexibility to rebalance a portfolio, if required, although they are subject to potential redemption limits (i.e., gates). Secondary transactions can also be effective in managing portfolios—not only to trim positioning, but also to add vintage year exposure, potentially at a discount commensurate with a correcting market.

The Long View

Private markets are a long-term asset class, and investors should structure their allocations and rebalancing policies accordingly. For investors in need of liquidity or rebalancing, ongoing innovations in private markets are providing new tools and optionality.

1 Refers to the dynamic of the private market portion of the portfolio increasing in relative size due to a decrease in the overall size of the portfolio (i.e., the denominator)