The New Math of Private Equity Value Creation

Surveys have shown that investors continue to view private equity as a critical component of their portfolios.1 The asset class may offer an important route for accessing long-term economic growth opportunities via a large universe of companies that are outside the publicly traded markets. Private equity may also help to drive innovation and evolution in the way companies operate. At today’s inflection points across technology, sustainability, and geopolitics, we believe many companies and industries must undergo dramatic transformation to thrive in the next decade and beyond.

However, we acknowledge that in an era that may be defined by slower economic growth, shrinking labor forces, and higher inflation than the past decade, investors and operators will likely have to contend with impacts from headwinds to revenue growth, margin compression, and a structurally higher cost of capital resulting from higher interest rates. We believe that private equity can continue to create attractive value for investors in this environment, but that the future path to value creation will be different than in the past.

A History of Private Equity Value Creation

Private equity is predicated on active, control-oriented ownership, which allows General Partners (GPs) to reshape acquired companies, their balance sheets, and strategic plans. This approach has enabled the private equity industry to generate 15% internal rates of return (IRR) over the past 10 and 20 years2—although performance has varied, both across managers and over time, such as around significant transitions in the macroeconomic cycle.

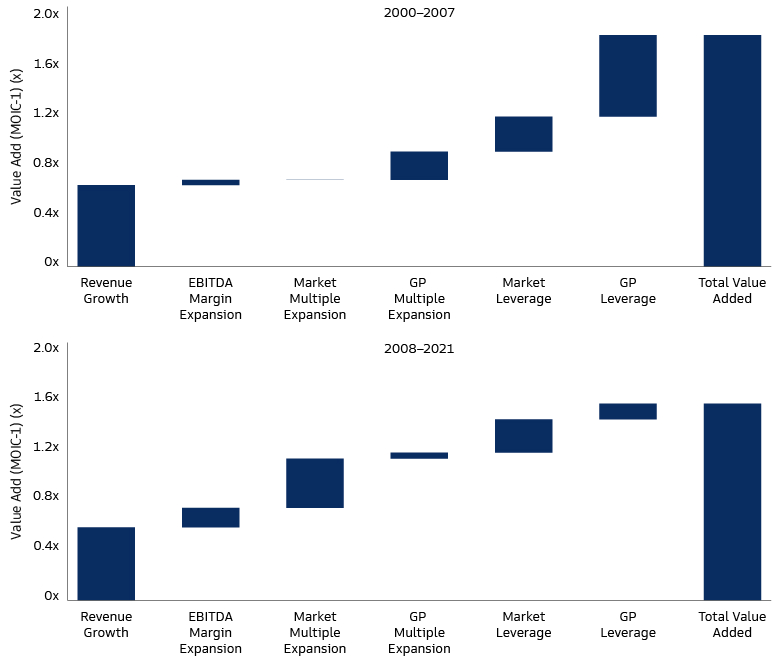

While approaches to executing a buyout investment vary widely, the drivers of return can be broadly classified into four categories: revenue growth, margin expansion, changes in valuations (e.g., multiple of EBITDA paid to acquire the company vs. received upon sale), and the use of financial structuring and leverage. Data shows that as the market environment evolved over the past four decades, private equity GPs adapted their value creation playbook to emphasize different return drivers. Leverage and financial structuring have become less important in recent decades, for example, while multiple expansion and operational factors have gained prominence.3

The Beginning: Leaning on Leverage

The buyout industry as we know it today began to coalesce in the 1980s,4 when tailwinds from tax and regulatory changes, combined with the development of leveraged loans, led to the advent of the “leveraged buyout” (LBO). The term itself suggests that leverage (debt) is a key component of the strategy—and in fact, leverage was the primary driver of returns in those early days. Academic studies have shown LBOs done prior to 1992 were structured with Debt/Value ratios in the range of 0.65-0.85x.5

With high leverage acting as the primary value creation driver, buyouts in this era generally focused on aggressively slashing costs in their portfolio companies, to maximize cash flows for debt repayment. In many cases, the underlying companies had been operating inefficiently, making cost savings a straightforward endeavor. However, such an aggressive leverage structure left little room for operational stumbles. Relatively small declines in revenue growth or margins could wipe out the entire equity investment. A number of prominent LBO-owned businesses went bankrupt in 1990-1992. A 1993 study showed that among the 83 large LBOs completed between 1985 and 1989, 26 defaulted and 18 entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings.6

Second Era: Fundamentals in Focus

In the next era, between the dot-com bust and the global financial crisis, private equity began its evolution to the industry of today. GPs pursued a more prudent capital structure, moving towards a more even split between debt and equity. In recent years, equity has made up as much as half of the overall financing in LBO transactions.

Against this market backdrop, GPs’ value creation strategy shifted towards generating greater value at the enterprise level, taking a longer-term view. Focus turned to driving revenue growth and margin expansion—unlocking untapped potential in underperforming businesses, fine-tuning operations of healthier companies, and building scale through add-on acquisitions. Some private equity firms began hiring dedicated operating professionals to work alongside their portfolio companies’ management teams to unlock value. As a result of these efforts, private equity managers have been able to generate superior operating performance in their portfolio companies, in aggregate, than was experienced in public markets.7 According to a 2021 academic study, revenue growth has been the most persistent source of value creation since 2000—contributing more than one-third to overall value-add, both before and since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).8

Post-Crisis: Riding the Beta Wave

Multiple expansion has also served as an important contributor to overall buyout value creation over the past 20 years. This factor has been particularly important since the GFC, with buyout deals seeing as much as 2-4x turns of EBITDA expansion from entry to exit.9 This multiple expansion has come through a combination of market-based (beta) effects and GP-specific (alpha) effects, such as improved company quality and growth prospects (see chart for more detail). Another effect has been evidenced in the frequently-employed buy-and-build (platform) strategies, wherein the manager combines a portfolio company with multiple smaller companies in the same business line. Because smaller companies tend to transact at lower valuations, this strategy averages down the cost basis for the consolidated enterprise.

Academic analyses attribute the multiple expansion in the period between the dot-com crash and the GFC primarily to the effects of GPs’ efforts. Conversely, the analyses suggest that multiple expansion since the GFC has been attributable primarily to market-based effects (given the significant run-up in public company multiples during this period), accounting for a quarter of overall value created for buyout deals executed since 2008.10 Nevertheless, GP-based multiple expansion added value in this period as well; the fact that buyout exit multiples have been consistently above acquisition multiples in a given year serves as evidence of alpha effects.11

While multiple expansion played a meaningful role in value enhancement at the industry level over the past decade, our analysis suggests that it alone was insufficient to generate above-median private equity returns historically. According to our analysis, in order to achieve top-half performance, revenues would have had to grow by at least 7% annually (assuming nominal impact from margin expansion)—above the level experienced by publicly traded US companies in the 2010s.12

Source: Matteo Binfare, Gregory Brown, Andra Ghent, Wendy Hu, Christian Lundblad, Richard Maxwell, Shawn Munday, and Lu Yi, “Performance Analysis and Attribution with Alternative Investments”, as of January 24, 2022.

Uncharted Territory: New Math for the Road Ahead

We believe the next ten years are unlikely to look like the last ten. The upcoming era may be defined by slower economic growth, shrinking labor forces, and higher inflation than the past decade—leaving investors and operators to contend with impacts from headwinds to topline real growth, margin compression, and a structurally higher cost of capital resulting from higher interest rates. Against this backdrop, we believe that private equity managers will continue to be able to generate attractive returns. However, the radically altered investment backdrop means that the path to value creation will need to look different than may have been the case in the past. Leverage and multiple expansion are unlikely to add as much to value creation as they have previously. Operational value creation levers—revenue growth and margin expansion—are poised to become the main determinants of success in the new regime.

Based on our analysis, at today’s cost of capital, a lower entry multiple, and without the benefit of multiple expansion, a company could generate low double-digit EBITDA growth to achieve the same return as with high single-digit EBITDA growth in the pre-COVID period. Our analysis also suggests that value creation is more sensitive to margin expansion than revenue growth. But while margin expansion may be powerful, it has been the more difficult lever to achieve, which may explain its relatively small contribution to value creation in the past 20 years.

It may be that companies need to flip the value creation playbook, if the less-used historical lever is more likely to generate future marginal benefits. For instance, companies in high-growth areas may now need to focus on margins as economic tailwinds abate, while investments in traditional sectors may need to generate topline growth as an environment of structurally higher inflation may impede margin expansion. These types of initiatives require different skillsets, so operating teams may need to expand their execution capabilities beyond those they’ve relied on in the past. The value of an experienced and knowledgeable investment partner, with both extensive operational networks to support management teams and the financial resources for the upfront costs of driving impactful transformation, should become increasingly apparent.

Revenue Growth: Going Organic

Platform strategies, M&A and add-on activity have historically driven a significant portion of historical revenue growth in private equity—and this trend has only intensified in the post-GFC era. Add-ons accounted for over three-quarters of US buyout transactions in 2022, up from 50% in 2008.13 However, going forward, higher interest rates may impact financing availability for such transactions, and growing anti-trust regulatory scrutiny may limit rollup opportunities in some sectors. Therefore, while we anticipate that add-ons will continue to be an important strategy for value creation even once financing markets normalize, we also believe that relying solely on inorganic growth will no longer be sufficient.

As such, we believe organic growth will become even more important for value creation in the years ahead. This growth could potentially be achieved by fixing broken business models or by super-charging growth in healthy, but slower-growing, businesses and industries. Organic growth may be accomplished by gaining market share in existing areas through better products, services or customer experiences; expanding into new markets by launching new products, entering new geographies, and targeting new client segments; and/or having a more analytical, data-driven pricing strategy to optimize revenues from each transaction. This will require more finely-honed capabilities and talent around brand building and communication, sales channel optimization, and market research. It will likely mean more technology capex and R&D spend to create new products and optimize existing ones.

Expanding at the Margin: A Renewed Focus on Operational Efficiency

Over the past several years, many private equity-owned companies have been able to pass through higher costs to customers, but the limits of price increases are beginning to be felt, with revenue growth outstripping increases in EBITDA in 2022.14 With elevated (though moderating) inflation and labor cost increases continuing to be in the forefront of macroeconomic statistics, margin expansion—and, indeed, the threat of margin contraction—is receiving increased attention.

Margin expansion can be an impactful value creation lever, and with the correct approach, can become a more meaningful contributor to value creation than was the case in the past. For some GPs, a focus on margins may represent a shift in mindset from prioritizing growth to now focusing on efficiency as the cost of capital has risen.

Margin enhancement is likely to rely on optimizing processes, enhancing supply chains, and rationalizing the workforce to be prepared for technological challenges and opportunities. GPs will need to question everything—from marketing budgets and the structure of sales organizations to raw material procurement and logistics—in order to understand the most efficient ways to drive growth, customer acquisition costs and unit economics. This effort will likely need more systems, processes, and technology to accurately understand costs, quantify their impact, and identify prudent ways of reducing expenses without hurting topline growth.

Technology: Time to Upgrade

Fortunately, today’s environment also offers tools for transformation that were not available in the last decade. Data science, AI, robotics, and automation continue to mature and accelerate. They are increasingly in a position to drive revenue growth and enhance efficiency in ways not possible before. As such, they are providing opportunities to effect large-scale business transformation while forcing a re-imagining of the characteristics of successful businesses. This may be especially valuable for businesses and industries that are performing well but below potential.

However, we believe technology as a standalone thesis is not sufficient to drive returns. Success is predicated on strategy and execution—implementing the correct processes, structures, and frameworks to harness technology. Cautionary tales abound of companies that spent heavily on technology without reaping the full benefits due to organizational frictions. As more companies lean into similar technological theses, the use of technology will cease to become a key differentiator. Over time, what are now novel technologies (including AI) will become a requirement rather than a competitive advantage. GPs need to not only work to create first-mover advantage and build a defensible moat, but also form a realistic view on the ability of technology to expand or create new markets—which may vary by technology and product/service type. This all adds complexity and cost to executing on a value creation plan.

These initiatives often require capex at a time when the cost of capital has increased, and the costs of transformation tend to be front-loaded while the benefits accrue over time. As a result, either GPs will need to extend holding periods to benefit from these upfront costs or find ways to reap the benefits of transformation faster. Execution timelines may need to speed up—with more of the work done in the diligence and underwriting phase than the post-acquisition phase, requiring closer collaboration between the GP’s investment and operating teams. In addition, GPs can seek out capital solutions to expedite some distributions to investors. While the use of leverage and financial structuring is unlikely to drive returns going forward, expertise in optimizing capital structures and managing certain macro risks (e.g., interest rates, FX) will be increasingly important to optimize cash flow and overall value of assets. We believe demand can continue to grow for innovative capital structures spanning the spectrum from senior credit to preferred and traditional equity, with the mix potentially evolving over the life of the deal. This dynamic may facilitate the growth of the all-weather strategic solutions strategy.

Why Take the Hard Road?

All companies, regardless of ownership structure, will likely face higher capital costs, headwinds for multiple expansion and a more challenging operating environment. It is likely, however, that private equity is advantaged relative to public markets in effecting large-scale company transformation. A long-term time horizon that allows for mid-journey pivots and adjustments as necessary, a more streamlined governance model in which a single owner makes resource allocation decisions, and additional resources that the GP can potentially deploy over time may all prove a decisive advantage in weathering a challenging environment. To the extent that new value-creation skills and competencies need to be developed, private equity GPs can amortize them over a broader capital base—a portfolio of companies, rather than an individual company.

As such, we continue to believe that private equity, with the right partner, should present attractive investment opportunities for investor portfolios. However, dynamics of the new environment will have implications for GPs around how to think about their competitive advantages and for LPs in terms of how to select managers.

In a period of acute uncertainty, we believe great investors will differentiate themselves by their confidence in what they can transform, a humility to accurately assess their abilities to create value and the discipline to price deals accordingly, and the ability to admit when they are wrong and change course.

1 See, for example, Goldman Sachs Asset Management 2023 Private Markets Diagnostic Survey. As of September 24, 2023.

2 Cambridge Associates. Pooled buyout IRRs over 10-year and 20-year periods through Q4 2022. Metrics are shown as of December 31, 2022 for the past 10 year and 20 year period. Like all trackers of fund data, such results do not represent the complete universe of private markets funds. As such, the databases referenced may face bias risks such as survivorship bias and non-reporting bias risks which may lead to higher overall returns than if such biases did not exist. IRR does not reflect the performance of any financial product offered by Goldman Sachs Asset Management. Past performance does not predict future returns and does not guarantee future results, which may vary.

3 Matteo Binfare, Gregory Brown, Andra Ghent, Wendy Hu, Christian Lundblad, Richard Maxwell, Shawn Munday, and Lu Yi, “Performance Analysis and Attribution with Alternative Investments.” As of January 24, 2022.

4 “Private equity, history and further development.” Harvard University. As of December 27, 2008.

5 Matteo Binfare, Gregory Brown, Andra Ghent, Wendy Hu, Christian Lundblad, Richard Maxwell, Shawn Munday, and Lu Yi, “Performance Analysis and Attribution with Alternative Investments.” As of January 24, 2022.

6 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol 19 No 4. “Private Equity: Boom and Bust?” As of Fall 2007.

7 Cambridge Associates LLC Private Investments Database, FactSet Research Systems, and Frank Russell Company. Data from January 1, 2000 – March 31, 2022.

8 Matteo Binfare, Gregory Brown, Andra Ghent, Wendy Hu, Christian Lundblad, Richard Maxwell, Shawn Munday, and Lu Yi, “Performance Analysis and Attribution with Alternative Investments.” As of January 24, 2022.

9 Prof. Gregory Brown, IPC. “Debt and Leverage in Private Equity: A Survey of Existing Results and New Findings.” As of January 4, 2021. A 2x turn of EBITDA expansion means that, for instance, a company that may have been purchased at a price equal to 10x the EBITDA it was generating at the time of acquisition would have been sold at 12x the EBITDA it was generating at the time of sale.

10 Matteo Binfare, Gregory Brown, Andra Ghent, Wendy Hu, Christian Lundblad, Richard Maxwell, Shawn Munday, and Lu Yi, “Performance Analysis and Attribution with Alternative Investments.” As of January 24, 2022.

11 Burgiss Company Fundamentals Review. As of 4Q 2022.

12 Based on S&P 500 aggregate revenue annual growth rates as reported by Dr. Edward Yardeni: “Corporate Finance Briefing: S&P 500 Revenues & Earnings Growth Rate.” As of May 29, 2023.

13 PitchBook 2Q 2023 Private Equity Breakdown. As of June 30, 2023.

14 Burgiss. As of 1Q 2023.