Unpacking Private Equity Valuations and Returns

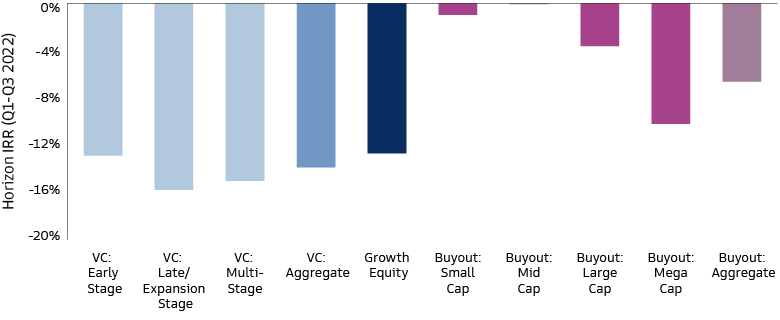

Private equity (PE) funds were down about 10% through the first three quarters of 2022, while public markets finished the year down roughly 20%.1 Initial reads of 4Q 2022 performance for private funds lead us to believe that the gap will persist. The discrepancy may lead some investors to question the validity of private market marks—which has happened during similar periods in the past. We believe much of the disconnect in valuations during public market dislocations comes from the way in which valuations are determined in PE, with nuances of different strategies impacting valuation dynamics.

PE strategies can experience periods of high beta but tend to see smaller markups and write-downs in quarters with large public market moves, such as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). During prior market selloffs, buyout-backed companies faced headwinds but were largely able to catch their footing, with GFC-vintage funds delivering below-average but still-positive returns. While the venture capital (VC) funds of the dot-com era never recovered, GFC-vintage VC and growth were also able to largely rebound in the recovery. Whether the same will be true today remains to be seen, but a review of common valuation practices helps put the current environment into context.

A Brief Primer on PE Valuations

Accounting rules dictate that PE GPs must establish quarterly marks that reflect the fair value of their current holdings. For assets that are not traded in public markets, such as PE, fair value is an estimate informed by the company’s operations and anchored in market dynamics; as such, it considers both fundamentals and sentiment factors. Within this framework, the GP can choose how to assess and weigh these factors, introducing subjectivity into the process. Investors commonly use three techniques to determine the fair value of an asset: discounted cash flow (DCF), public peer comparables, and precedent transactions. Depending on the strategy and the stage of company development, the approaches may differ.

DCF analysis projects cash flows until a future date, then assumes the investment will be sold at an estimated terminal value. Applying a discount rate to those cash flows from the terminal date back through today produces a valuation. The DCF analysis can be relatively immune to short-term public market valuation gyrations from shifting investor sentiment, but highly sensitive to the cash flow assumptions and discount rates being used. This can be even more pronounced for high-growth companies, where more of the value in the DCF model is in the terminal value, which gets impacted to a greater degree by the higher discount rate. Subjectivity centers on forecasts of future cash flows and the terminal value; the discount rate is based on more objective, observable cost of capital parameters.

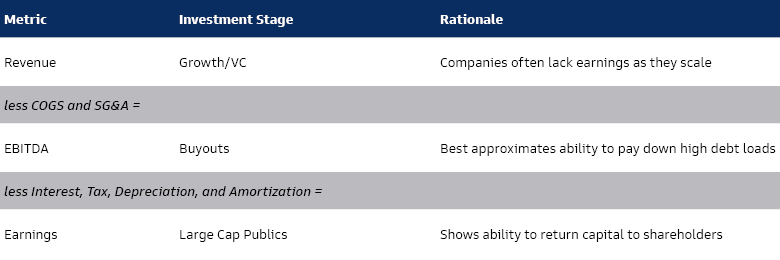

Comparable company analysis aims to identify public companies similar to the private asset in terms of industry and sector, business characteristics, and—to the extent practical—size, and to consider the multiples at which these companies are trading in the market. In essence, it seeks to allow holders of illiquid positions to assess the fair price of an asset if it were to be sold today. The appropriate metric will depend on the type of investment being pursued and the stage of development of the target company or asset.

Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only.

We believe subjectivity in this valuation technique centers on the companies selected as comparables and any potential adjustments that may be necessary. Many PE-backed companies may not have a robust set of true comparables in the public market, often because public counterparts are too large and diversified or the private companies operate in a niche not captured by GICS (Global Industry Classification Standards) sub-sectors. Another important consideration is the differing composition of public and private markets, which can meaningfully impact headline numbers. The S&P 500, for example, has less exposure to industrials, materials, and resources, which has favored PE in the current environment. And while they have similar exposure to information technology, PE is more oriented towards enterprise rather than consumer-facing businesses that have seen greater performance headwinds. There have been important performance differences across sizes too, with larger PE funds—which have closer public comps and more macro exposure—experiencing more significant write-downs than smaller vehicles.

Source: Cambridge Associates. As of September 30, 2022.

Growth rates are another complicating factor, as the higher growth rates often found in private markets can be difficult to model and compare to public markets. Comparable companies’ valuations may also figure in idiosyncratic factors. Due to these differences, identified comparable companies may trade at a wide range of multiples today, necessitating some subjectivity in reconciling those into one number.

Another potential drawback of public market comparables is that the metrics are susceptible to shifts in sentiment, which may not reflect operating fundamentals or longer-term value trends. Indeed, while public equity markets over the long term tend to track estimates of future earnings, the relationship is least reliable in volatile markets. Given the high level of noise observed over short periods, PE managers have some discretion when adjusting public market comparables for their specific investment, particularly if underlying fundamentals remain intact. The lagged nature of private markets also allows managers to filter out short-term market noise and sentiment shifts; if the public markets have already rebounded by the time private market valuations for the quarter are being established, GPs may curtail their multiple contraction in the current quarter and subsequently mute their expansion the following quarter. Of note, private markets tended to lag on the rebounds as well.

To help remove market noise, and because selling an ownership stake is quite different than trading liquid minority positions, private market investors often prefer to use recent transactions to establish comps. Valuation techniques and subjectivity parameters parallel those of public market comparables: identify available data on closely comparable companies, then adjust and triangulate to calculate a truly comparable multiple. Intermittent deal activity presents continual challenges to this method, particularly in down markets such as the current one when transaction data may be upwardly biased because dealmaking declines and concentrates in the highest quality assets. At the same time, it is impossible to accurately gauge what multiple could have theoretically been assigned to transactions that didn’t get done because the buyer and the seller could not agree on a price.

Buyouts tend to rely on all three metrics noted above, while earlier-stage venture and growth investments take a somewhat different approach to valuations. Growth equity investors generally benefit from being able to underwrite some level of financial operating performance in their investments, but more uncertainty about the magnitude and timing of cash flows largely deems DCFs less useful than in the buyout space. And while private growth-backed companies may have some similarities to public market firms, the private enterprises tend to be significantly smaller, less mature, and, most likely, faster-growing.

Many venture-backed startups do not even generate financials, let alone have public market peers. Unlike the dot-com era, however, when businesses were notoriously valued based on rudimentary metrics like “eyeballs,” today there are well-established metrics to measure tangible progress for startups lacking financials. In consumer software, for example, metrics including daily/monthly active users, churn, and detailed engagement profiles provide a richer view of how products are gaining traction; however, these metrics are still just signals and often lack strong comparable market data.

With these shortcomings rendering comparables somewhat less relevant, especially in the earliest stages, VC and growth investors rely more on precedent transactions – specifically, the value at which the company they own received its last capital injection. While funding rounds of companies at similar stages of development will be considered, the funding history of the target company often plays an outsized role. From that valuation, adjustments can be made to reflect progress made by the company in the interim, as well as the prevailing valuations for VC-backed companies at similar stages. While some investors make prudent adjustments for changes in fundamentals, valuations often are fairly sticky until the next funding round is on the horizon with some visibility into pricing. This works in both directions: valuations may prove conservative when the market is trending up but may appear overly optimistic when the market is trending down, as is the case today.

Valuations in Today’s Context

Buyouts

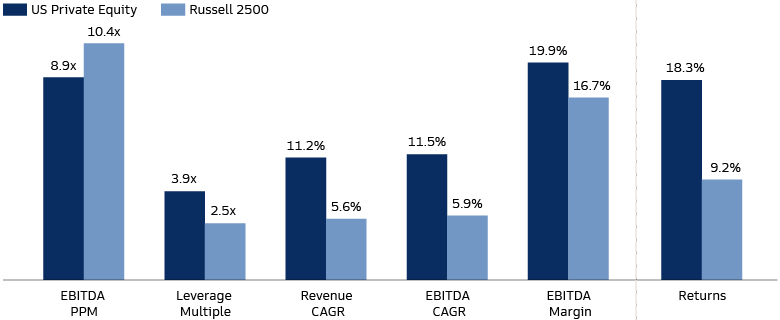

When explaining recent disparities in public and private performance, we believe it makes sense to start with the foundation of valuations: fundamentals. Historically, PE companies’ fundamentals have been more resilient than those of public companies due to a variety of factors. Some of the common reasons given for PE outperformance include close collaboration between owners and management, enhanced governance structures, and a long-term orientation. Furthermore, PE owners may have the capacity to finance acquisitions and/or provide a capital infusion to support growth or fortify the balance sheet.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC Private Investments Database, FactSet Research Systems, and Frank Russell Company. Data from January 1, 2000 – March 31, 2022

Even as macro headwinds accumulated in 2022, both earnings and revenue growth of buyout-backed companies have remained strong. The median buyout company grew revenues by almost 20% year over year (as of 3Q 2022), and EBITDA grew by over 10%.2 Performance so far has highlighted this resilience in a challenging environment. However, GPs must acknowledge meaningful headwinds: broader margin compression and higher interest expenses that may increase further as rates rise. As you can see in Riding the Tri-Cycle, market uncertainty remains high, requiring both GPs and portfolio companies to continue to evolve and adapt.

While EBITDA—the preferred metric of buyout investors—is unaffected by rising interest expenses, we believe managers need to honestly consider the longer-term impact of rising rates amidst a more challenging operating environment. With higher interest expenses, some companies may be left with less cash flow than budgeted for value-creation initiatives, while the most indebted will have little room for operational missteps before encountering distress. All this may warrant some valuation re-rating at the aggregate level as margins compress, but the ongoing operating strength thus far has given GPs little reason to significantly adjust valuations.

Venture / Growth

In VC and growth equity, we foresee a slow, gradual valuation adjustment rather than a severe move downwards as existing investors and founders meet new realities. The volume of new funding rounds, which typically inform valuations, has slowed drastically. Many management teams quickly and aggressively cut costs, shifting operational focus from growth to capital efficiency given the increased cost of capital. This has created more cash runway than expected and allowed many companies to forego expected financing. Still, there are companies that have spent down cash reserves and require additional financing, and the valuation environment has changed drastically given the rise in interest rates and broader economic headwinds.

Many companies raised capital at lofty valuations that will take time to grow into, even under optimistic scenarios. While their trajectory has changed, many are still reluctant to accept a lower valuation and the realities it brings, including dampening employee morale. For companies that require additional capital, many are opting for non-dilutive financing options that do not come with a valuation reset. Some high-profile and high-quality companies, however, are reportedly accepting reduced valuations to bring in the right partners and establish a more sustainable trajectory, which could help to thaw the market.

Over the longer term, today’s challenges will amplify differences between companies. The strongest and most developed companies maintain strong growth rates and margins, while others are struggling to adjust their business models and improve unit economics. In the long run, venture returns famously follow a power law distribution, with a small number of outliers driving a disproportionate share of returns. This characteristic of the strategy may lead to categorically aggressive valuations in aggregate, as investors underwrite to a large total addressable market. But while this may lead to potentially lofty valuations broadly, undoubtedly, there are VC-backed companies today that will transform industries—some are even commercially viable now, and growing fast, with lots of runway. We believe the question for investors is whether they have exposure to those outlier winners.

Assessing Individual Portfolios

Aggregate market data can be a helpful guide, but we believe the highly idiosyncratic nature of private market investing necessitates a deep look into the underlying trajectories of individual portfolios—particularly at a time when dispersion is on the rise. In addition to the raw fundamentals and comparable multiples, GPs consider a variety of other more qualitative factors. One is the underlying sources and drivers of value creation, and whether these are repeatable and sustainable as the environment shifts. The valuation can also be impacted by how the business model is positioned for the new environment, and whether value creation initiatives are feasible under new cost structures, where more resources may need to be allocated towards paying interest. GPs should be able to explain how different positions within the portfolio performed and justify relative differences both within the portfolio and with external sources. We believe comparisons should be made to both public market troughs and updated company trajectories.

We believe fund returns need to be assessed through multiple lenses to gain a full picture. As explained in Axiom of Choice: Measuring Private Market Performance, both IRR and MOIC should be analyzed, with different considerations depending on the specific stage of the fund life. IRR can appear elevated early if there are very early distributions, for example, but tends to settle close to the final absolute and relative level by around year seven. For MOIC, it’s also important to break out distributed value from remaining value. In robust markets, distributions increase as PE managers sell into strength. Funds also tend to markup existing assets, increasing both realized and unrealized returns.

When assessing a particular manager or fund, changes in historical marks can be a helpful guide. How did the GP value their positions during prior market cycles? Has the GP been aggressive or conservative in their historic marks relative to the eventual realization/exit? The manager’s broader fundraising cycle should also be considered, as research has shown GPs tendency to paint the most favorable picture of performance when preparing to launch a new fund.3

PE funds generated strong returns during the post-pandemic recovery, with newer funds posting mostly unrealized gains that may precipitate subsequent write-downs if companies are unable to achieve what is many cases were optimistic underwriting standards. Broadly, however, it appears that private market assets have continued to deliver strong operating performance, and owners have been willing and able to navigate a period with few liquidity opportunities.

1Cambridge Associates, as of September 2022. Refinitiv, as of December 31, 2022.

2Burgiss, as of September 30, 2022.

3Institutional Investor, Private Equity Firms ‘Try to Manipulate Their Performance’ When Raising Money, As of February 9, 2021