Tax-Loss Harvesting Strategies: How They Work

Frequently Asked Questions

Taxes: They can’t be avoided. But they can be managed. A tax-loss harvesting strategy may help you keep more of what you earn. Find out how it all works and why we think a customizable separately managed account can be an effective way to potentially maximize tax efficiency.

What is tax-loss harvesting?

Simply put, tax-loss harvesting is a strategy designed to potentially reduce your overall tax bill so you can keep more of what you earn from your investments. It works by selling investments at a loss and using those losses to offset some, or possibly all, of the capital gains from investments that you sold at a profit. For example, if an investor buys a stock at $400 and sells it for $500, they realize a capital gain of $100. This will trigger a capital gains tax (the amount will depend on variables such as the investor’s marginal tax rate, state and local tax rates and how long they held the stock). However, if the investor sells another security at a $100 loss, they can use that realized loss to offset the gain from the sale of the other stock. As a result, the net realized gain is reduced and the investor’s overall tax bill may be lowered.

OK, how might I apply tax-loss harvesting in an equity strategy?

We think a strong vehicle is a customizable separately managed account, or SMA, which may allow a manager to reduce your tax bill by “harvesting” losses while maintaining broad market exposure.

Here’s how it works:

- The SMA seeks to provide market-like returns through direct indexing, by purchasing a portfolio of diverse1 stocks resembling the broad equity market.

- The manager opportunistically sells stocks throughout the year that are trading at a loss. This happens when the stock price falls below the price at which it was purchased, also known as the investment’s “cost basis.”

- The manager then replaces those stocks with securities that have similar risk and return characteristics. For example, they may decide to sell the stock of a large financial institution that is trading at a loss and replace it with another stock or set of stocks—perhaps those issued by other large banks.

The realized losses are then used to offset capital gains incurred in other parts of the investor’s portfolio.

There are many ways for investors to end up with a tax bill at year end. Examples include investment gains from other active managers, capital gains distributions from mutual funds, selling appreciated real estate, private equity distributions or investing in hedge funds which may not be tax efficient.

So the manager’s job is to pick losing stocks?

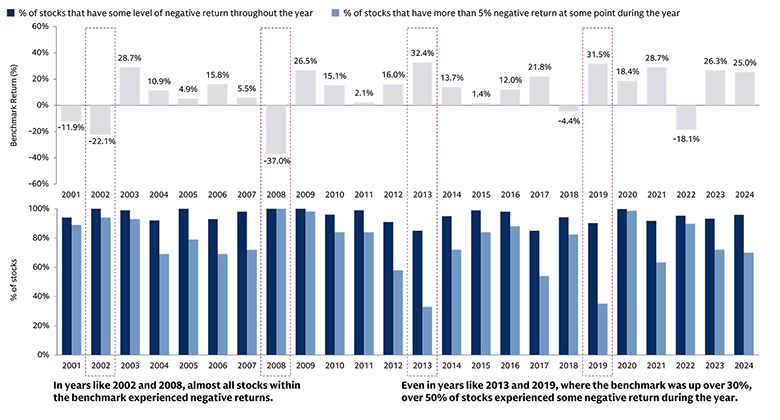

No, not at all. The purpose of tax-loss harvesting is not to pick losing stocks. It is simply to potentially help investors benefit from naturally occurring market volatility and dispersion in stock returns. Think about it this way: even in years when an index such as the S&P 500 delivers a positive return, not every single stock in the index has a positive return throughout the year. Some stocks experience losses throughout the year and may even end the year in the red.

While market returns vary from year to year, market volatility is a constant. Volatility and dispersion of stocks returns create potential opportunities to harvest losses which adds value to an investment portfolio by potentially increasing after-tax returns. Of course, the amount of potential tax savings depends on the market environment— typically, a year with low market returns will provide more harvesting opportunities than a high return year. But we believe tax-loss harvesting may work in any market environment because losses exist in all market environments.

Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Standard and Poor’s. As of December 31, 2024.

Aren’t other passive vehicles, such as ETFs and index funds, also tax efficient? What’s different about a tax-managed SMA?

ETFs generally have low expenses, and most are passively managed and structured to track an index. But when it comes to tax efficiency, there are three key differences.

- An ETF or index fund investor owns shares in a fund that tracks an index. With an ETF, an investor may only harvest a loss when the entire index is down. In contrast, the SMA investor directly owns many of the individual securities in the broad equity market. This is sometimes referred to as “direct indexing”. By owning all of the underlying securities, a manager can harvest losses when the index is down but can also opportunistically sell individual stocks trading at a loss in pursuit of higher tax savings and after-tax returns compared to an ETF.

- In an ETF or an index fund, all realized losses within the fund can only be used to offset realized gains within the fund. Whereas realized losses in a SMA, as noted earlier, can be used to offset gains anywhere else in an investor’s portfolio. This can potentially add up to greater tax savings.

- SMAs can generally be funded with both cash and in-kind stock contributions. Existing stock positions in an investor’s portfolio can be transitioned in-kind into an SMA and managed with greater tax efficiency.

What are the long-term potential benefits for an investment portfolio?

When repeated in a systematic way, year in and year out, tax-loss harvesting can potentially reduce your tax bill. That means an investor is not only saving money on their taxes in a given year, but they can reinvest those tax savings for potential growth in the future. And the longer a portfolio stays invested, the more time it has to grow and compound.

Can any type of investor potentially benefit from tax-loss harvesting strategies?

All taxable investors may potentially benefit from tax-loss harvesting strategies and investors in the highest tax brackets stand to potentially benefit the most. This is because the higher the tax bracket, the bigger the potential savings. It also helps to have capital gains from other parts of an investor’s portfolio. This could include gains from selling down concentrated stock, private equity or other active managers. If an investor doesn’t have capital gains from other investments in a particular year, harvested losses can be used to offset $3,0002 in ordinary income per year. This includes interest, wages, dividends and net income from a business. Any excess losses can be carried forward indefinitely and used to offset capital gains in the future.

Investors who may want to consider tax-loss harvesting include those who plan to donate their portfolio to charity or bequest it to heirs, as this would not involve realizing capital gains. Investors who plan to liquidate their portfolio eventually would then pay taxes on realized gains. But if they employed tax-loss harvesting over a long investment horizon, they may find that the portfolio appreciated more than it would have had it been invested in an index strategy without tax management.

To explore how we can help you with tax-advantaged investment opportunities, visit our Goldman Sachs Asset Management Tax-Advantaged Strategies webpage.

1 Diversification does not protect an investor from market risk and does not ensure a profit.

2 See Capital Losses: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i1040sd.pdf